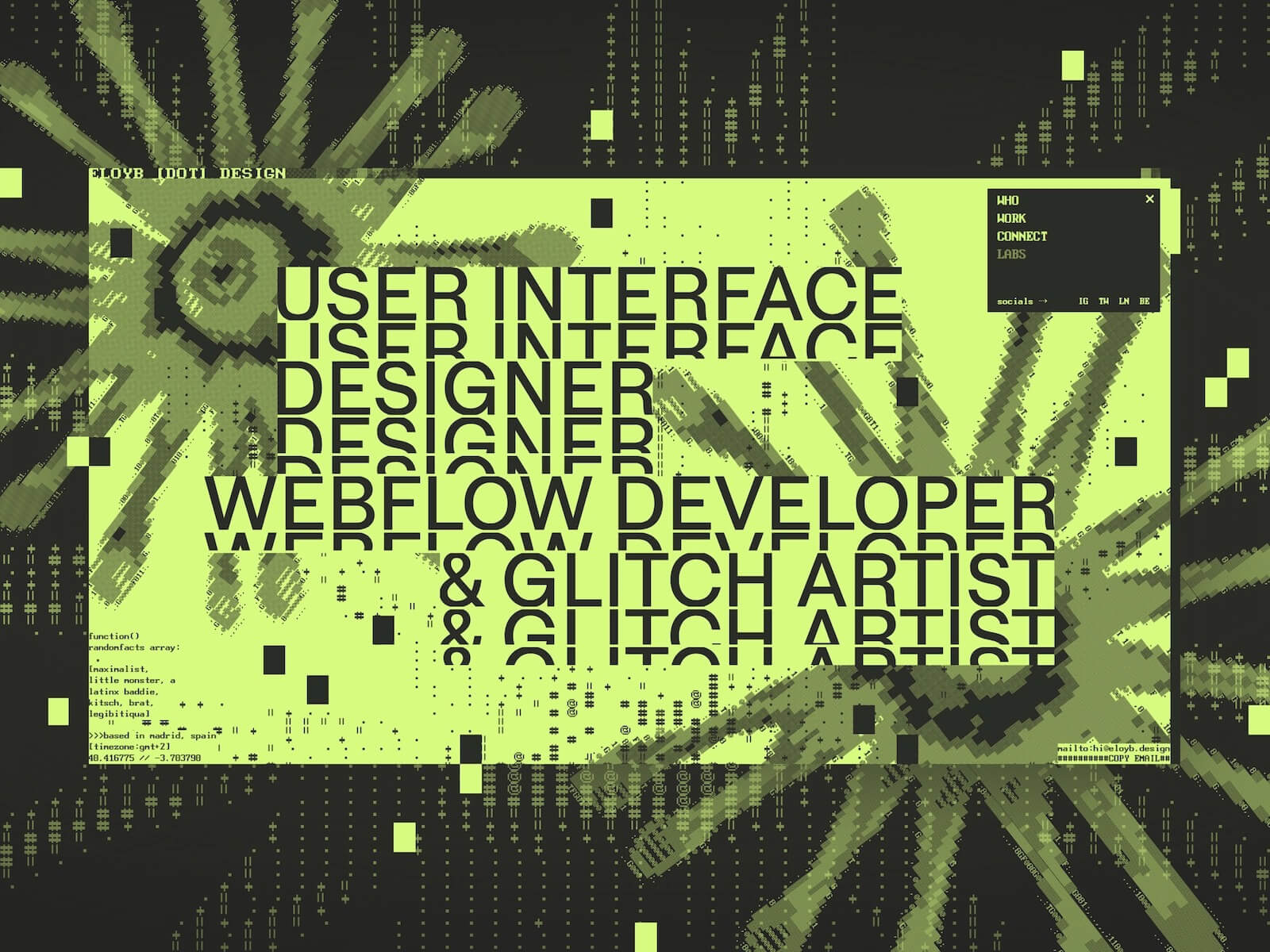

Hello World, Eloy Benoffi here (also known as ē𝔩๏ȳ̶̮̰̈́b) from Mar del Plata, Argentina — currently based in Madrid, Spain. I’m an Experimental UI Designer, Webflow Developer, and sometimes I like to call myself a Glitch Artist. In this case study, I will walk you through the vision and implementation behind my 2025 Portfolio Site.

It all began with one prompt: “I really, really need to update my portfolio.”

As some of you will know, this might be one of the hardest tasks to land on a creative’s desk. I’d had the same very simple minimalist site online since 2022 which, to be honest, really helped people find me, but no longer represented my vibes or the type of creative work I aim for. So I asked myself: how can I build something that not only showcases my projects and serves as a connector with potential clients, but also truly translates my ideas of pushing boundaries, opposing the norm, and having fun while doing it?

The answer didn’t come easily; I went through 16 iterations in Figma, experimenting non-stop for almost a year until I found the biggest piece of inspo within my own previous work. This ultimately helped shape the whole visual universe of my new site.

An Unapologetically Glitchy Web Experience

Experimenting and discarding ideas wasn’t in vain; some of them were not that good, some of them were lost gems, and a bunch of them found new life and got reworked into the final design. In retrospect, I now see clearly how each trial and error helped me refine the three key ideas behind my choices for this project:

Maximalism: More is more. I decided I wouldn’t back down, I wouldn’t scale down features or details for clarity, and I wouldn’t let austerity enter this project unless absolutely needed.

Brutalism: Things will be what they will be, and they don’t need to be perfect or subtle. I will allow each element to be bold, rough, and in your face. Shapes can be sharp, glitches can be glitchy, and everything should try to be brutally honest.

Fun: We should never forget to have fun in our personal projects. I internalized this like a mantra: “This is for you — you can do anything you want with it. The only constraints are your own whims; try to release expectations on how it’ll be perceived by your peers, and just build what you want to build. If potential clients don’t get it, then they’re probably not a match for you; the ones who get it will bring projects where you can feel authentic in your work.”

I tried to keep these notions in mind while designing the final iteration of the site, which was the one I felt happiest about.

A Tech Stack for Creating Mayhem

Once the design was ready, I had to bring it to life.

As a Webflow Certified Partner, I knew from the start that this would be the natural choice to build the site, as it allows me to put together complex HTML and CSS layouts in an easy and comprehensive way.

I love this platform because it helps to build better and faster, but doesn’t get in the way if you want to mess with custom code, and it’s great at allowing you to take things a step further beyond its core capabilities.

I knew that motion would be a key element — not just as decoration, but as a way to guide attention, create rhythm, and reinforce the three ideas behind the visuals. GSAP was the clear choice for me to animate. Its flexibility allowed me to experiment freely, from creating micro-interactions to large transitions and complex timelines. GSAP Plugins aided every step of the way, and thanks to them releasing all their premium plugins for free, I was able to use quite a few of them:

I’ll be sharing some code snippets below so you can take a peek at how I built my animations.

Wow at First Sight: The Loading Animation into the Hero Section

I based the design on my piece Nature is Watching, reusing the eye-flower assets and ASCII versions of them as decoration. I wanted the intro section to feel like an animated expansion of this piece, while also including relevant information about me, what I do, where I come from, and how to contact me.

The idea behind the loader animation was to start with a stripped-down version of the full visuals and then add elements as the container expands. The whole section is scaled down while a loading bar grows, which later becomes the navbar.

Location Easter Egg

Once the content is loaded, there’s a tiny easter egg in the location element (bottom left). I wanted to include both my current location (Madrid) and my birthplace (Mar del Plata), so when you hover over it, the text switches between these location names, time zones, and coordinates.

This was done with very straightforward JavaScript. First, I created a function to change the Madrid location’s text to Mar del Plata’s, which contains a GSAP timeline and uses the Text Plugin to handle the text content changes. Secondly, I added an event listener that triggers the function on mouseenter:

function setLocationMardel() {

let LocationToMardel = gsap.timeline();

LocationToMardel.fromTo(

"[location-type-01][type-txt]",

{

text: {

value: ">>>based in madrid, spain",

},

},

{

text: {

value: ">>>born in mar del plata, arg",

speed: 1,

preserveSpaces: true,

padSpace: true,

type: "diff",

},

duration: 0.3,

ease: "none",

},

0

)

.fromTo(

"[location-type-02][type-txt]",

{

text: {

value: "[timezone:gmt+2]",

},

},

{

text: {

value: "[timezone:gmt-3]",

speed: 1,

preserveSpaces: true,

padSpace: true,

type: "diff",

},

duration: 0.3,

ease: "none",

},

0

)

.fromTo(

"[location-type-03][type-txt]",

{

text: {

value: "40.416775 // -3.703790",

},

},

{

text: {

value: "-37.979858 // -57.589794",

preserveSpaces: true,

padSpace: true,

speed: 1,

type: "diff",

},

duration: 0.3,

ease: "none",

},

0

);

}const heroMeta = document.querySelector(".hero-meta");

heroMeta.addEventListener("mouseenter", () => {

setLocationMardel();

});Plucking an SVG Flower

As you leave the hero by scrolling down, the backdrop ASCII flower starts losing its characters. This was made possible thanks to SVG and GSAP ScrollTrigger. I targeted the individual paths inside the SVG graphic and then staggered them out as you scroll through the container:

let tlHeroSVG = gsap.timeline({

scrollTrigger: {

trigger: '.hero-section',

start: 'top bottom',

end: 'bottom-=50% top',

scrub: 8,

},

});

tlHeroSVG.to('.hero-flower_03 path', {

stagger: {

each: 0.1,

from: 'random',

},

opacity: 0,

duration: 2,

ease: 'bounce.inOut',

});

Here, Look at My Work

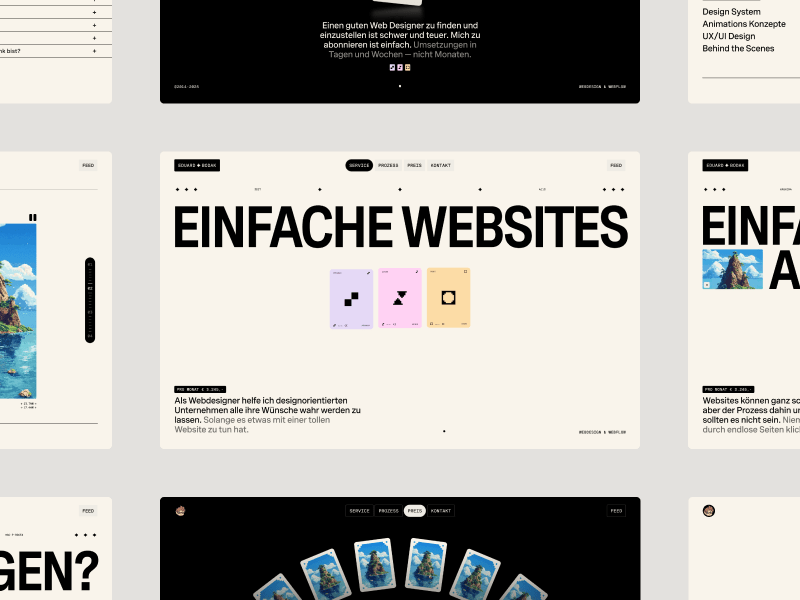

After the complexity of the Hero section, one might be tempted to chill out and let the user relax — but that would go against my more is more anthem. When reaching the Work section, you’ll see that it might be the most minimalist section of the site, in the sense that there are fewer elements. However, I tried to make them stand out through movement. I used two main animations to keep up the attention:

Creating a Mesmerizing Title

The heading of this section serves both as a title reading “Selected Work” and as a transition between the chaos of the hero and the work content. To craft this animation, I set up several rows of divs with overflow: hidden at three different heights. Inside each one, there are at least three copies of the “Selected Work” text stacked vertically. I created a simple GSAP timeline with ScrollTrigger and staggers to move their yPercent with different easings while scrolling down, creating this fluid effect.

let tlWorkScroll = gsap.timeline({

scrollTrigger: {

trigger: '.work-section',

start: 'top bottom',

end: 'bottom-=60% top',

scrub: 0.6,

},

});

tlWorkScroll.fromTo(

'.work-header .title-row_33 .title-txt',

{

yPercent: 0,

},

{

yPercent: -300,

ease: 'power3.in',

duration: 2,

stagger: {

amount: 2,

from: 'start',

},

},

0

);

tlWorkScroll.fromTo(

'.work-header .title-row_66 .title-txt',

{

yPercent: 0,

},

{

yPercent: -300,

ease: 'power2.in',

duration: 2,

stagger: {

amount: 2,

from: 'start',

},

},

0

);

tlWorkScroll.fromTo(

'.work-header .title-row_main .title-txt',

{

yPercent: 0,

},

{

yPercent: -300,

ease: 'power1.in',

duration: 2,

stagger: {

amount: 2,

from: 'start',

},

},

0

);

A Rude Introduction to My Work

My selected projects are laid out in horizontal sliders made with the Draggable and Inertia plugins. I wanted something out of the ordinary to reveal their content, so I created a four-step timeline that sets the scale of each visible graphic randomly through these scale values: 1.75 → 1.5 → 1.25 → 1, with a tiny 0.15s delay between steps.

To add more chaos to it, I set the transform-origin of each graphic to different positions so the scaling effect wouldn’t be homogeneous.

tlWorkCardReveal.fromTo(

wCardItems,

{

scale: 1.75,

},

{

scale: 1.5,

duration: 0.25,

ease: 'power3.in',

stagger: {

amount: 0.2,

from: 'random',

ease: 'power1.out',

},

},

0

);

tlWorkCardReveal.fromTo(

wCardItems,

{

scale: 1.5,

},

{

scale: 1.25,

duration: 0.2,

ease: 'power3.inOut',

stagger: {

amount: 0.15,

from: 'random',

ease: 'power1.inOut',

},

},

'>=-0.15'

);

tlWorkCardReveal.fromTo(

wCardItems,

{

scale: 1.25,

},

{

scale: 1,

duration: 0.15,

ease: 'power3.out',

stagger: {

amount: 0.1,

from: 'random',

ease: 'power1.out',

},

},

'>=-0.15'

);

Ending with a Critical Error

After these intense animations, I couldn’t just finish the site with a simple footer. Instead, I brought back the ASCII decorations, forced the menu to open, and implemented a cloning machine linked to the mouse movement.

There’s just one button element — a very simple div with a background color and the text “CLICK TO CONNECT” inside it. Using JavaScript, I created a function that duplicates the element twice each time the mouse moves 200px in any direction, up to a limit of 200 copies, and positions the clones in random absolute places. The button div has a CSS blending-mode set to “difference” to make the overlap more visually interesting when the colors collide. Then, when the mouse leaves the footer element, all copies are removed.

Each new batch of copies enters and leaves with a staggered GSAP animation and custom backIn easing:

gsap.to(generatedCopies, {

opacity: 0,

scale: 0.6,

duration: 0.2,

ease: 'back.in(1.7)',

stagger: {

amount: 0.4,

from: 'random',

ease: 'power1.out',

},

});Some Final Thoughts

Though I tried to release external expectations with this experiment, I couldn’t help but be a bit scared of how it would be received. It sparked some conversations on social media about marketing vs. art, minimalism vs. maximalism, and where the line is drawn on usability. There were a few detractors who were very concerned with conversion, and also a few people who totally got it.

The truth is that building this portfolio was less about shipping a polished marketing shopfront and more about creating a space for me to use as a playground — a place where my design style, coding skills, and idiosyncrasy could collide into the kind of extra and glitchy site I wanted to see on the web. Bugs or accidental mistakes became features, animations ran a little too wild, and I did my best to take everything one step beyond. It was fun!

After launching, my site was recognized with an Awwwards Honorable Mention, GSAP Site of the Day, and CSSDA Best UI, Best UX, Best Innovation, and Special Kudos.

Ending on a personal note, I feel that in this new era of AI-generated content and sales-optimized templates, we should provide space for human authenticity, intentionality, and even errors — qualities that will likely be more relevant than ever moving forward.

Thanks for reading about my process. If you leave my site with a spark of intrigue, a smile at the chaos, or the urge to break a few rules in your own work, then my mission was accomplished — and you already know you can always Click to Connect.