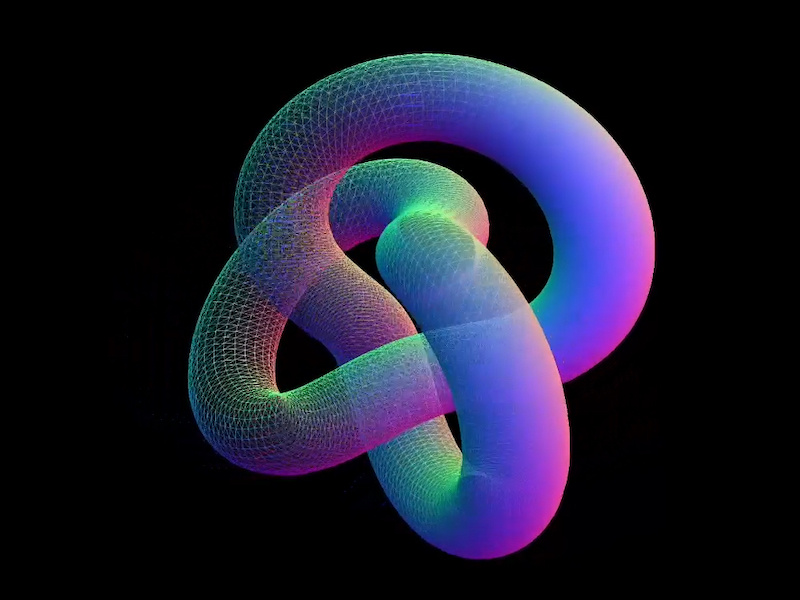

Blackbird was a fun, experimental site that I used as a way to get familiar with WebGL inside of Solid.js. It went through the story of how the SR-71 was built in super technical detail. The wireframe effect covered here helped visualize the technology beneath the surface of the SR-71 while keeping the polished metal exterior visible that matched the sites aesthetic.

Here is how the effect looks like on the Blackbird site:

In this tutorial, we’ll rebuild that effect from scratch: rendering a model twice, once as a solid and once as a wireframe, then blending the two together in a shader for a smooth, animated transition. The end result is a flexible technique you can use for technical reveals, holograms, or any moment where you want to show both the structure and the surface of a 3D object.

There are three things at work here: material properties, render targets, and a black-to-white shader gradient. Let’s get into it!

But First, a Little About Solid.js

Solid.js isn’t a framework name you hear often, I’ve switched my personal work to it for the ridiculously minimal developer experience and because JSX remains the greatest thing since sliced bread. You absolutely don’t need to use the Solid.js part of this demo, you could strip it out and use vanilla JS all the same. But who knows, you may enjoy it 🙂

Intrigued? Check out Solid.js.

Why I Switched

TLDR: Full-stack JSX without all of the opinions of Next and Nuxt, plus it’s like 8kb gzipped, wild.

The technical version: Written in JSX, but doesn’t use a virtual DOM, so a “reactive” (think useState()) doesn’t re-render an entire component, just one DOM node. Also runs isomorphically, so "use client" is a thing of the past.

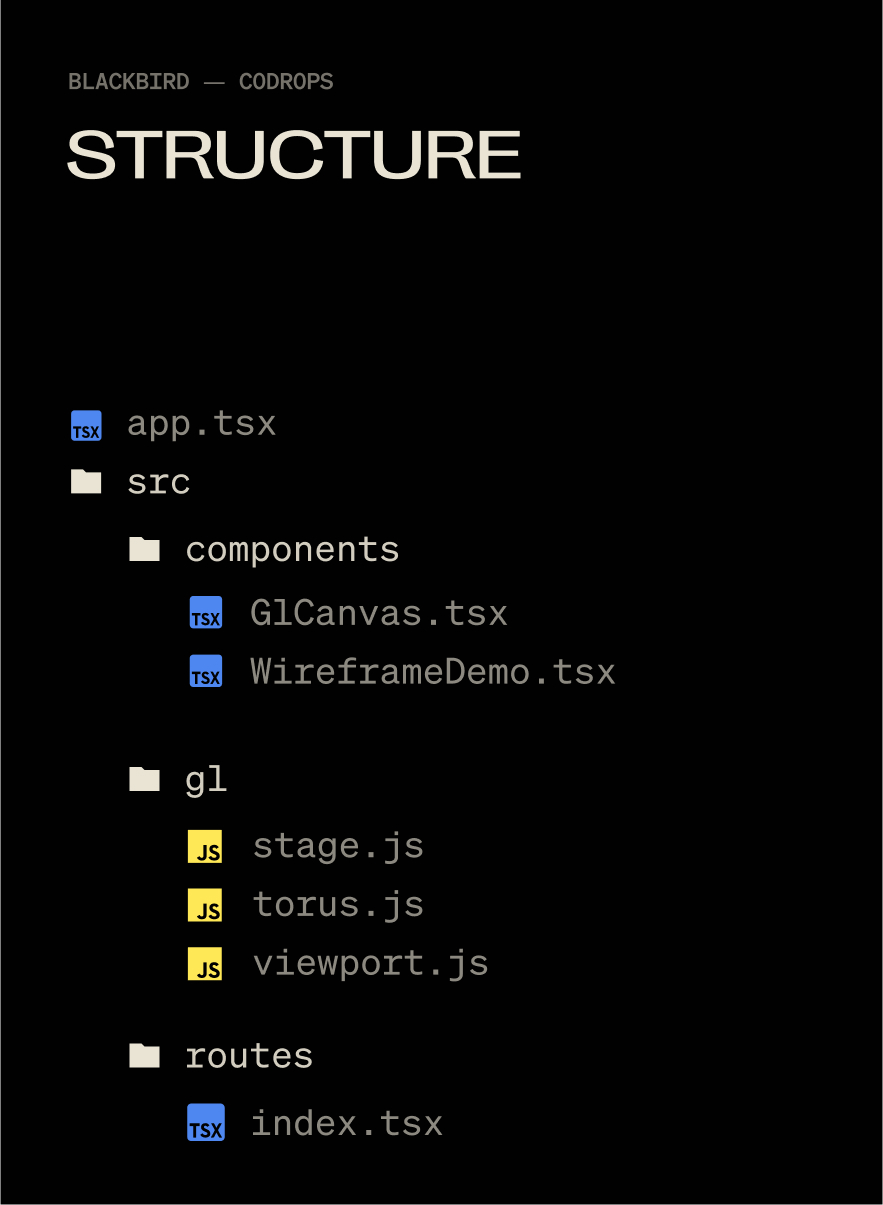

Setting Up Our Scene

We don’t need anything wild for the effect: a Mesh, Camera, Renderer, and Scene will do. I use a base Stage class (for theatrical-ish naming) to control when things get initialized.

A Global Object for Tracking Window Dimensions

window.innerWidth and window.innerHeight trigger document reflow when you use them (more about document reflow here). So I keep them in one object, only updating it when necessary and reading from the object, instead of using window and causing reflow. Notice these are all set to 0 and not actual values by default. window gets evaluated as undefined when using SSR, so we want to wait to set this until our app is mounted, GL class is initialized, and window is defined to avoid everybody’s favorite error: Cannot read properties of undefined (reading ‘window’).

// src/gl/viewport.js

export const viewport = {

width: 0,

height: 0,

devicePixelRatio: 1,

aspectRatio: 0,

};

export const resizeViewport = () => {

viewport.width = window.innerWidth;

viewport.height = window.innerHeight;

viewport.aspectRatio = viewport.width / viewport.height;

viewport.devicePixelRatio = Math.min(window.devicePixelRatio, 2);

};A Basic Three.js Scene, Renderer, and Camera

Before we can render anything, we need a small framework to handle our scene setup, rendering loop, and resizing logic. Instead of scattering this across multiple files, we’ll wrap it in a Stage class that initializes the camera, renderer, and scene in one place. This makes it easier to keep our WebGL lifecycle organized, especially once we start adding more complex objects and effects.

// src/gl/stage.js

import { WebGLRenderer, Scene, PerspectiveCamera } from 'three';

import { viewport, resizeViewport } from './viewport';

class Stage {

init(element) {

resizeViewport() // Set the initial viewport dimensions, helps to avoid using window inside of viewport.js for SSR-friendliness

this.camera = new PerspectiveCamera(45, viewport.aspectRatio, 0.1, 1000);

this.camera.position.set(0, 0, 2); // back the camera up 2 units so it isn't on top of the meshes we make later, you won't see them otherwise.

this.renderer = new WebGLRenderer();

this.renderer.setSize(viewport.width, viewport.height);

element.appendChild(this.renderer.domElement); // attach the renderer to the dom so our canvas shows up

this.renderer.setPixelRatio(viewport.devicePixelRatio); // Renders higher pixel ratios for screens that require it.

this.scene = new Scene();

}

render() {

this.renderer.render(this.scene, this.camera);

requestAnimationFrame(this.render.bind(this));

// All of the scenes child classes with a render method will have it called automatically

this.scene.children.forEach((child) => {

if (child.render && typeof child.render === 'function') {

child.render();

}

});

}

resize() {

this.renderer.setSize(viewport.width, viewport.height);

this.camera.aspect = viewport.aspectRatio;

this.camera.updateProjectionMatrix();

// All of the scenes child classes with a resize method will have it called automatically

this.scene.children.forEach((child) => {

if (child.resize && typeof child.resize === 'function') {

child.resize();

}

});

}

}

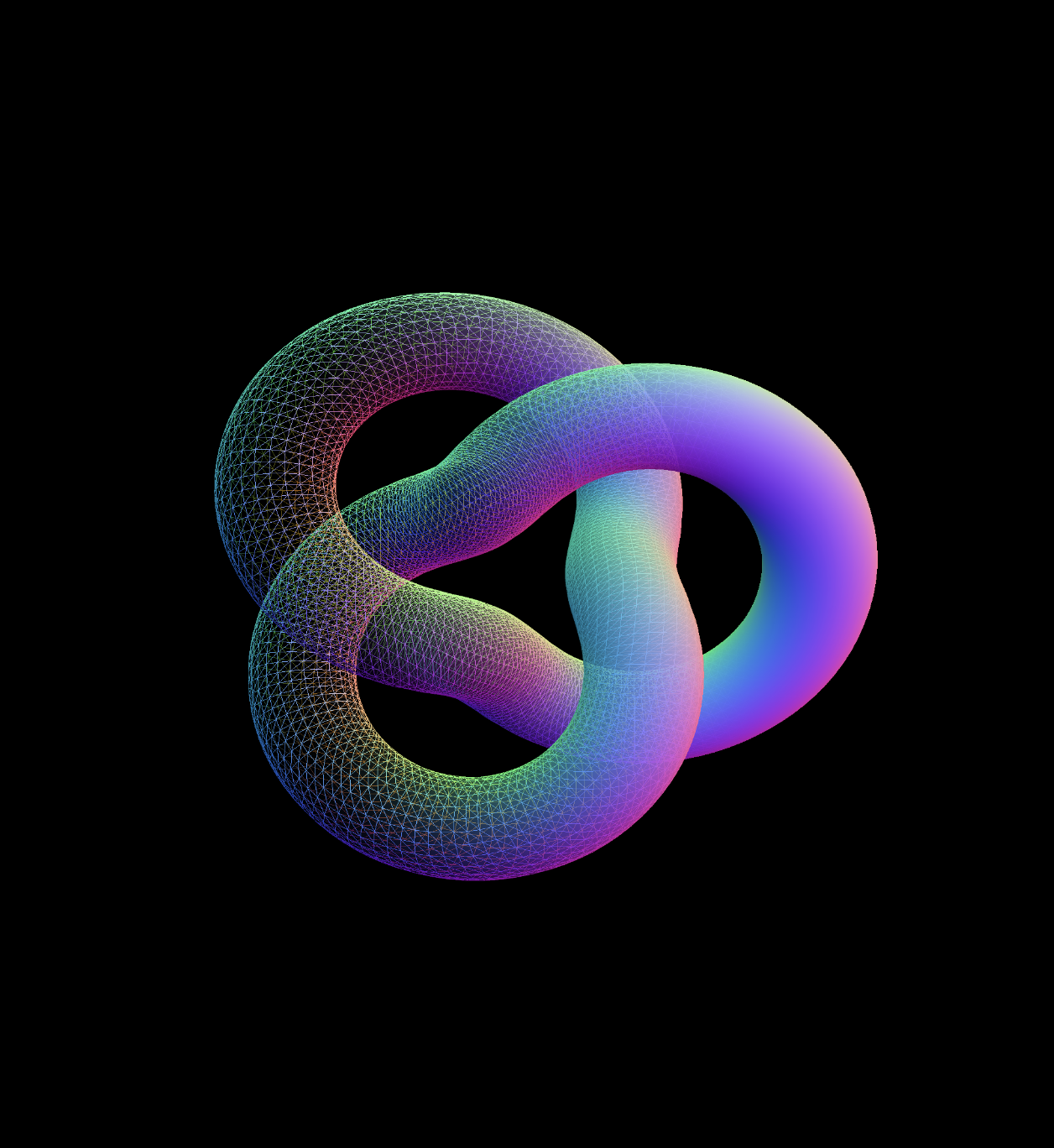

export default new Stage();And a Fancy Mesh to Go With It

With our stage ready, we can give it something interesting to render. A torus knot is perfect for this: it has plenty of curves and detail to show off both the wireframe and solid passes. We’ll start with a simple MeshNormalMaterial in wireframe mode so we can clearly see its structure before moving on to the blended shader version.

// src/gl/torus.js

import { Mesh, MeshBasicMaterial, TorusKnotGeometry } from 'three';

export default class Torus extends Mesh {

constructor() {

super();

this.geometry = new TorusKnotGeometry(1, 0.285, 300, 26);

this.material = new MeshNormalMaterial({

color: 0xffff00,

wireframe: true,

});

this.position.set(0, 0, -8); // Back up the mesh from the camera so its visible

}

}A quick note on lights

For simplicity we’re using MeshNormalMaterial so we don’t have to mess with lights. The original effect on Blackbird had six lights, waaay too many. The GPU on my M1 Max was choked to 30fps trying to render the complex models and realtime six-point lighting. But reducing this to just 2 lights (which visually looked identical) ran at 120fps no problem. Three.js isn’t like Blender where you can plop in 14 lights and torture your beefy computer with the render for 12 hours while you sleep. The lights in WebGL have consequences 🫠

Now, the Solid JSX Components to House It All

// src/components/GlCanvas.tsx

import { onMount, onCleanup } from 'solid-js';

import Stage from '~/gl/stage';

export default function GlCanvas() {

// let is used instead of refs, these aren't reactive

let el;

let gl;

let observer;

onMount(() => {

if(!el) return

gl = Stage;

gl.init(el);

gl.render();

observer = new ResizeObserver((entry) => gl.resize());

observer.observe(el); // use ResizeObserver instead of the window resize event.

// It is debounced AND fires once when initialized, no need to call resize() onMount

});

onCleanup(() => {

if (observer) {

observer.disconnect();

}

});

return (

<div

ref={el}

style={{

position: 'fixed',

inset: 0,

height: '100lvh',

width: '100vw',

}}

/>

);

}let is used to declare a ref, there is no formal useRef() function in Solid. Signals are the only reactive method. Read more on refs in Solid.

Then slap that component into app.tsx:

// src/app.tsx

import { Router } from '@solidjs/router';

import { FileRoutes } from '@solidjs/start/router';

import { Suspense } from 'solid-js';

import GlCanvas from './components/GlCanvas';

export default function App() {

return (

<Router

root={(props) => (

<Suspense>

{props.children}

<GlCanvas />

</Suspense>

)}

>

<FileRoutes />

</Router>

);

}Each 3D piece I use is tied to a specific element on the page (usually for timeline and scrolling), so I create an individual component to control each class. This helps me keep organized when I have 5 or 6 WebGL moments on one page.

// src/components/WireframeDemo.tsx

import { createEffect, createSignal, onMount } from 'solid-js'

import Stage from '~/gl/stage';

import Torus from '~/gl/torus';

export default function WireframeDemo() {

let el;

const [element, setElement] = createSignal(null);

const [actor, setActor] = createSignal(null);

createEffect(() => {

setElement(el);

if (!element()) return;

setActor(new Torus()); // Stage is initialized when the page initially mounts,

// so it's not available until the next tick.

// A signal forces this update to the next tick,

// after Stage is available.

Stage.scene.add(actor());

});

return <div ref={el} />;

}createEffect() instead of onMount(): this automatically tracks dependencies (element, and actor in this case) and fires the function when they change, no more useEffect() with dependency arrays 🙃. Read more on createEffect in Solid.

Then a minimal route to put the component on:

// src/routes/index.tsx

import WireframeDemo from '~/components/WiframeDemo';

export default function Home() {

return (

<main>

<WireframeDemo />

</main>

);

}

Now you’ll see this:

Switching a Material to Wireframe

I loved wireframe styling for the Blackbird site! It fit the prototype feel of the story, fully textured models felt too clean, wireframes are a bit “dirtier” and unpolished. You can wireframe just about any material in Three.js with this:

// /gl/torus.js

this.material.wireframe = true

this.material.needsUpdate = true;

But we want to do this dynamically on only part of our model, not on the entire thing.

Enter render targets.

The Fun Part: Render Targets

Render Targets are a super deep topic but they boil down to this: Whatever you see on screen is a frame for your GPU to render, in WebGL you can export that frame and re-use it as a texture on another mesh, you are creating a “target” for your rendered output, a render target.

Since we’re going to need two of these targets, we can make a single class and re-use it.

// src/gl/render-target.js

import { WebGLRenderTarget } from 'three';

import { viewport } from '../viewport';

import Torus from '../torus';

import Stage from '../stage';

export default class RenderTarget extends WebGLRenderTarget {

constructor() {

super();

this.width = viewport.width * viewport.devicePixelRatio;

this.height = viewport.height * viewport.devicePixelRatio;

}

resize() {

const w = viewport.width * viewport.devicePixelRatio;

const h = viewport.height * viewport.devicePixelRatio;

this.setSize(w, h)

}

}This is just an output for a texture, nothing more.

Now we can make the class that will consume these outputs. It’s a lot of classes, I know, but splitting up individual units like this helps me keep track of where stuff happens. 800 line spaghetti mega-classes are the stuff of nightmares when debugging WebGL.

// src/gl/targeted-torus.js

import {

Mesh,

MeshNormalMaterial,

PerspectiveCamera,

PlaneGeometry,

} from 'three';

import Torus from './torus';

import { viewport } from './viewport';

import RenderTarget from './render-target';

import Stage from './stage';

export default class TargetedTorus extends Mesh {

targetSolid = new RenderTarget();

targetWireframe = new RenderTarget();

scene = new Torus(); // The shape we created earlier

camera = new PerspectiveCamera(45, viewport.aspectRatio, 0.1, 1000);

constructor() {

super();

this.geometry = new PlaneGeometry(1, 1);

this.material = new MeshNormalMaterial();

}

resize() {

this.targetSolid.resize();

this.targetWireframe.resize();

this.camera.aspect = viewport.aspectRatio;

this.camera.updateProjectionMatrix();

}

}Now, switch our WireframeDemo.tsx component to use the TargetedTorus class, instead of Torus:

// src/components/WireframeDemo.tsx

import { createEffect, createSignal, onMount } from 'solid-js';

import Stage from '~/gl/stage';

import TargetedTorus from '~/gl/targeted-torus';

export default function WireframeDemo() {

let el;

const [element, setElement] = createSignal(null);

const [actor, setActor] = createSignal(null);

createEffect(() => {

setElement(el);

if (!element()) return;

setActor(new TargetedTorus()); // << change me

Stage.scene.add(actor());

});

return <div ref={el} data-gl="wireframe" />;

}“Now all I see is a blue square Nathan, it feel like we’re going backwards, show me the cool shape again”.

Shhhhh, It’s by design I swear!

From MeshNormalMaterial to ShaderMaterial

We can now take our Torus rendered output and smack it onto the blue plane as a texture using ShaderMaterial. MeshNormalMaterial doesn’t let us use a texture, and we’ll need shaders soon anyway. Inside of targeted-torus.js remove the MeshNormalMaterial and switch this in:

// src/gl/targeted-torus.js

this.material = new ShaderMaterial({

vertexShader: `

varying vec2 v_uv;

void main() {

gl_Position = projectionMatrix * modelViewMatrix * vec4(position, 1.0);

v_uv = uv;

}

`,

fragmentShader: `

varying vec2 v_uv;

varying vec3 v_position;

void main() {

gl_FragColor = vec4(0.67, 0.08, 0.86, 1.0);

}

`,

});Now we have a much prettier purple plane with the help of two shaders:

- Vertex shaders manipulate vertex locations of our material, we aren’t going to touch this one further

- Fragment shaders assign the colors and properties to each pixel of our material. This shader tells every pixel to be purple

Using the Render Target Texture

To show our Torus instead of that purple color, we can feed the fragment shader an image texture via uniforms:

// src/gl/targeted-torus.js

this.material = new ShaderMaterial({

vertexShader: `

varying vec2 v_uv;

void main() {

gl_Position = projectionMatrix * modelViewMatrix * vec4(position, 1.0);

v_uv = uv;

}

`,

fragmentShader: `

varying vec2 v_uv;

varying vec3 v_position;

// declare 2 uniforms

uniform sampler2D u_texture_solid;

uniform sampler2D u_texture_wireframe;

void main() {

// declare 2 images

vec4 wireframe_texture = texture2D(u_texture_wireframe, v_uv);

vec4 solid_texture = texture2D(u_texture_solid, v_uv);

// set the color to that of the image

gl_FragColor = solid_texture;

}

`,

uniforms: {

u_texture_solid: { value: this.targetSolid.texture },

u_texture_wireframe: { value: this.targetWireframe.texture },

},

});And add a render method to our TargetedTorus class (this is called automatically by the Stage class):

// src/gl/targeted-torus.js

render() {

this.material.uniforms.u_texture_solid.value = this.targetSolid.texture;

Stage.renderer.render(this.scene, this.camera);

Stage.renderer.setRenderTarget(this.targetSolid);

Stage.renderer.clear();

Stage.renderer.setRenderTarget(null);

}THE TORUS IS BACK. We’ve passed our image texture into the shader and its outputting our original render.

Mixing Wireframe and Solid Materials with Shaders

Shaders were black magic to me before this project. It was my first time using them in production and I’m used to frontend where you think in boxes. Shaders are coordinates 0 to 1, which I find far harder to understand. But, I’d used Photoshop and After Effects with layers plenty of times. These applications do a lot of the same work shaders can: GPU computing. This made it far easier. Starting out by picturing or drawing what I wanted, thinking how I might do it in Photoshop, then asking myself how I could do it with shaders. Photoshop or AE into shaders is far less mentally taxing when you don’t have a deep foundation in shaders.

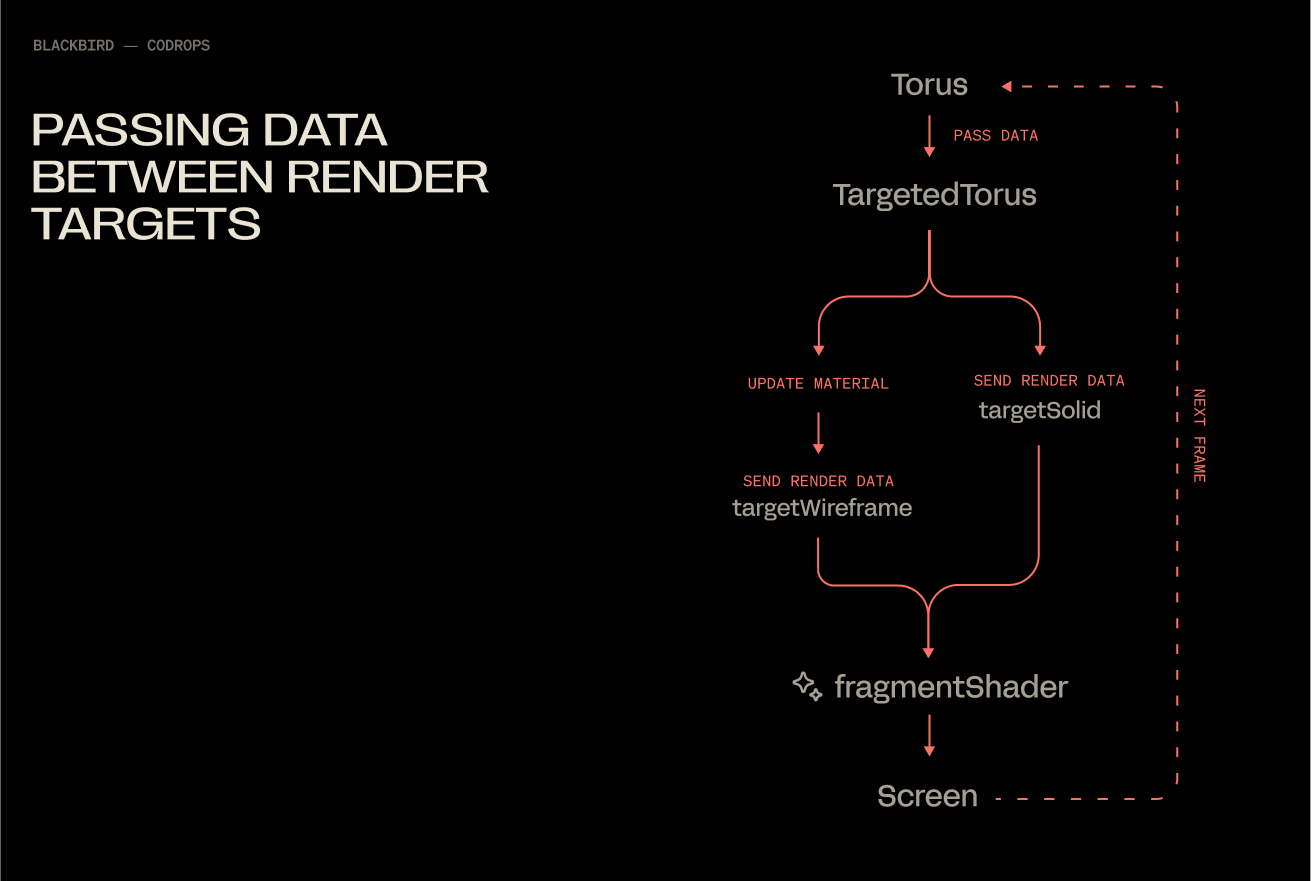

Populating Both Render Targets

At the moment, we are only saving data to the solidTarget render target via normals. We will update our render loop, so that our shader has them both this and wireframeTarget available simultaneously.

// src/gl/targeted-torus.js

render() {

// Render wireframe version to wireframe render target

this.scene.material.wireframe = true;

Stage.renderer.setRenderTarget(this.targetWireframe);

Stage.renderer.render(this.scene, this.camera);

this.material.uniforms.u_texture_wireframe.value = this.targetWireframe.texture;

// Render solid version to solid render target

this.scene.material.wireframe = false;

Stage.renderer.setRenderTarget(this.targetSolid);

Stage.renderer.render(this.scene, this.camera);

this.material.uniforms.u_texture_solid.value = this.targetSolid.texture;

// Reset render target

Stage.renderer.setRenderTarget(null);

}With this, you end up with a flow that under the hood looks like this:

Fading Between Two Textures

Our fragment shader will get a little update, 2 additions:

- smoothstep creates a linear ramp between 2 values. UVs only go from 0 to 1, so in this case we use

.15and.65as the limits (they look make the effect more obvious than 0 and 1). Then we use the x value of the uvs to define which value gets fed into smoothstep. vec4 mixed = mix(wireframe_texture, solid_texture, blend);mix does exactly what it says, mixes 2 values together at a ratio determined by blend..5being a perfectly even split.

// src/gl/targeted-torus.js

fragmentShader: `

varying vec2 v_uv;

varying vec3 v_position;

// declare 2 uniforms

uniform sampler2D u_texture_solid;

uniform sampler2D u_texture_wireframe;

void main() {

// declare 2 images

vec4 wireframe_texture = texture2D(u_texture_wireframe, v_uv);

vec4 solid_texture = texture2D(u_texture_solid, v_uv);

float blend = smoothstep(0.15, 0.65, v_uv.x);

vec4 mixed = mix(wireframe_texture, solid_texture, blend);

gl_FragColor = mixed;

}

`,And boom, MIXED:

Let’s be honest with ourselves, this looks exquisitely boring being static so we can spice this up with little magic from GSAP.

// src/gl/torus.js

import {

Mesh,

MeshNormalMaterial,

TorusKnotGeometry,

} from 'three';

import gsap from 'gsap';

export default class Torus extends Mesh {

constructor() {

super();

this.geometry = new TorusKnotGeometry(1, 0.285, 300, 26);

this.material = new MeshNormalMaterial();

this.position.set(0, 0, -8);

// add me!

gsap.to(this.rotation, {

y: 540 * (Math.PI / 180), // needs to be in radians, not degrees

ease: 'power3.inOut',

duration: 4,

repeat: -1,

yoyo: true,

});

}

}Thank You!

Congratulations, you’ve officially spent a measurable portion of your day blending two materials together. It was worth it though, wasn’t it? At the very least, I hope this saved you some of the mental gymnastics orchestrating a pair of render targets.

Have questions? Hit me up on Twitter!