Tests are as important as production code. Well, they are even more important! So writing them well brings lots of benefits to your projects.

Table of Contents

Just a second! 🫷

If you are here, it means that you are a software developer.

So, you know that storage, networking, and domain management have a cost .If you want to support this blog, please ensure that you have disabled the adblocker for this site.

I configured Google AdSense to show as few ADS as possible – I don’t want to bother you with lots of ads, but I still need to add some to pay for the resources for my site.Thank you for your understanding.

– Davide

Clean code principles apply not only to production code but even to tests. Indeed, a test should be even more clean, easy-to-understand, and meaningful than production code.

In fact, tests not only prevent bugs: they even document your application! New team members should look at tests to understand how a class, a function, or a module works.

So, every test must have a clear meaning, must have its own raison d’être, and must be written well enough to let the readers understand it without too much fuss.

In this last article of the Clean Code Series, we’re gonna see some tips to improve your tests.

If you are interested in more tips about Clean Code, here are the other articles:

Why you should keep tests clean

As I said before, tests are also meant to document your code: given a specific input or state, they help you understand what the result will be in a deterministic way.

But, since tests are dependent on the production code, you should adapt them when the production code changes: this means that tests must be clean and flexible enough to let you update them without big issues.

If your test suite is a mess, even the slightest update in your code will force you to spend a lot of time updating your tests: that’s why you should organize your tests with the same care as your production code.

Good tests have also a nice side effect: they make your code more flexible. Why? Well, if you have a good test coverage, and all your tests are meaningful, you will be more confident in applying changes and adding new functionalities. Otherwise, when you change your code, you will not be sure not only that the new code works as expected, but that you have not introduced any regression.

So, having a clean, thorough test suite is crucial for the life of your application.

How to keep tests clean

We’ve seen why we should write clean tests. But how should you write them?

Let’s write a bad test:

[Test]

public void CreateTableTest()

{

//Arrange

string tableContent = @"<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>ColA</th>

<th>ColB</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>Text1A</td>

<td>Text1B</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Text2A</td>

<td>Text2B</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>";

var tableInfo = new TableInfo(2);

HtmlDocument doc = new HtmlDocument();

doc.LoadHtml(tableContent);

var node = doc.DocumentNode.ChildNodes[0];

var part = new TableInfoCreator(node);

var result = part.CreateTableInfo();

tableInfo.SetHeaders(new string[] { "ColA", "ColB" });

tableInfo.AddRow(new string[] { "Text1A", "Text1B" });

tableInfo.AddRow(new string[] { "Text2A", "Text2B" });

result.Should().BeEquivalentTo(tableInfo);

}

This test proves that the CreateTableInfo method of the TableInfoCreator class parses correctly the HTML passed in input and returns a TableInfo object that contains info about rows and headers.

This is kind of a mess, isn’t it? Let’s improve it.

Use appropriate test names

What does CreateTableTest do? How does it help the reader understand what’s going on?

We need to explicitly say what the tests want to achieve. There are many ways to do it; one of the most used is the Given-When-Then pattern: every method name should express those concepts, possibly in a consistent way.

I like to use always the same format when naming tests: {Something}_Should_{DoSomething}_When_{Condition}. This format explicitly shows what and why the test exists.

So, let’s change the name:

[Test]

public void CreateTableInfo_Should_CreateTableInfoWithCorrectHeadersAndRows_When_TableIsWellFormed()

{

//Arrange

string tableContent = @"<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>ColA</th>

<th>ColB</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>Text1A</td>

<td>Text1B</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Text2A</td>

<td>Text2B</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>";

var tableInfo = new TableInfo(2);

HtmlDocument doc = new HtmlDocument();

doc.LoadHtml(tableContent);

HtmlNode node = doc.DocumentNode.ChildNodes[0];

var part = new TableInfoCreator(node);

var result = part.CreateTableInfo();

tableInfo.SetHeaders(new string[] { "ColA", "ColB" });

tableInfo.AddRow(new string[] { "Text1A", "Text1B" });

tableInfo.AddRow(new string[] { "Text2A", "Text2B" });

result.Should().BeEquivalentTo(tableInfo);

}

Now, just by reading the name of the test, we know what to expect.

Initialization

The next step is to refactor the tests to initialize all the stuff in a better way.

The first step is to remove the creation of the HtmlNode seen in the previous example, and move it to an external function: this will reduce code duplication and help the reader understand the test without worrying about the HtmlNode creation details:

[Test]

public void CreateTableInfo_Should_CreateTableWithHeadersAndRows_When_TableIsWellFormed()

{

//Arrange

string tableContent = @"<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>ColA</th>

<th>ColB</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>Text1A</td>

<td>Text1B</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Text2A</td>

<td>Text2B</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>";

var tableInfo = new TableInfo(2);

// HERE!

HtmlNode node = CreateNodeElement(tableContent);

var part = new TableInfoCreator(node);

var result = part.CreateTableInfo();

tableInfo.SetHeaders(new string[] { "ColA", "ColB" });

tableInfo.AddRow(new string[] { "Text1A", "Text1B" });

tableInfo.AddRow(new string[] { "Text2A", "Text2B" });

result.Should().BeEquivalentTo(tableInfo);

}

private static HtmlNode CreateNodeElement(string content)

{

HtmlDocument doc = new HtmlDocument();

doc.LoadHtml(content);

return doc.DocumentNode.ChildNodes[0];

}

Then, depending on what you are testing, you could even extract input and output creation into different methods.

If you extract them, you may end up with something like this:

[Test]

public void CreateTableInfo_Should_CreateTableWithHeadersAndRows_When_TableIsWellFormed()

{

var node = CreateWellFormedHtmlTable();

var part = new TableInfoCreator(node);

var result = part.CreateTableInfo();

TableInfo tableInfo = CreateWellFormedTableInfo();

result.Should().BeEquivalentTo(tableInfo);

}

private static TableInfo CreateWellFormedTableInfo()

{

var tableInfo = new TableInfo(2);

tableInfo.SetHeaders(new string[] { "ColA", "ColB" });

tableInfo.AddRow(new string[] { "Text1A", "Text1B" });

tableInfo.AddRow(new string[] { "Text2A", "Text2B" });

return tableInfo;

}

private HtmlNode CreateWellFormedHtmlTable()

{

var table = CreateWellFormedTable();

return CreateNodeElement(table);

}

private static string CreateWellFormedTable()

=> @"<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>ColA</th>

<th>ColA</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>Text1A</td>

<td>Text1B</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Text2A</td>

<td>Text2B</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>";

So, now, the general structure of the test is definitely better. But, to understand what’s going on, readers have to jump to the details of both CreateWellFormedHtmlTable and CreateWellFormedTableInfo.

Even worse, you have to duplicate those methods for every test case. You could do a further step by joining the input and the output into a single object:

public class TableTestInfo

{

public HtmlNode Html { get; set; }

public TableInfo ExpectedTableInfo { get; set; }

}

private TableTestInfo CreateTestInfoForWellFormedTable() =>

new TableTestInfo

{

Html = CreateWellFormedHtmlTable(),

ExpectedTableInfo = CreateWellFormedTableInfo()

};

and then, in the test, you simplify everything in this way:

[Test]

public void CreateTableInfo_Should_CreateTableWithHeadersAndRows_When_TableIsWellFormed()

{

var testTableInfo = CreateTestInfoForWellFormedTable();

var part = new TableInfoCreator(testTableInfo.Html);

var result = part.CreateTableInfo();

TableInfo tableInfo = testTableInfo.ExpectedTableInfo;

result.Should().BeEquivalentTo(tableInfo);

}

In this way, you have all the info in a centralized place.

But, sometimes, this is not the best way. Or, at least, in my opinion.

In the previous example, the most important part is the elaboration of a specific input. So, to help readers, I usually prefer to keep inputs and outputs listed directly in the test method.

On the contrary, if I had to test for some properties of a class or method (for instance, test that the sorting of an array with repeated values works as expected), I’d extract the initializations outside the test methods.

AAA: Arrange, Act, Assert

A good way to write tests is to write them with a structured and consistent template. The most used way is the Arrange-Act-Assert pattern:

That means that in the first part of the test you set up the objects and variables that will be used; then, you’ll perform the operation under test; finally, you check if the test passes by using assertion (like a simple Assert.IsTrue(condition)).

I prefer to explicitly write comments to separate the 3 parts of each test, like this:

[Test]

public void CreateTableInfo_Should_CreateTableWithHeadersAndRows_When_TableIsWellFormed()

{

// Arrange

var testTableInfo = CreateTestInfoForWellFormedTable();

TableInfo expectedTableInfo = testTableInfo.ExpectedTableInfo;

var part = new TableInfoCreator(testTableInfo.Html);

// Act

var actualResult = part.CreateTableInfo();

// Assert

actualResult.Should().BeEquivalentTo(expectedTableInfo);

}

Only one assertion per test (with some exceptions)

Ideally, you may want to write tests with only a single assertion.

Let’s take as an example a method that builds a User object using the parameters in input:

public class User

{

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

public DateTime BirthDate { get; set; }

public Address AddressInfo { get; set; }

}

public class Address

{

public string Country { get; set; }

public string City { get; set; }

}

public User BuildUser(string name, string lastName, DateTime birthdate, string country, string city)

{

return new User

{

FirstName = name,

LastName = lastName,

BirthDate = birthdate,

AddressInfo = new Address

{

Country = country,

City = city

}

};

}

Nothing fancy, right?

So, ideally, we should write tests with a single assert (ignore in the next examples the test names – I removed the when part!):

[Test]

public void BuildUser_Should_CreateUserWithCorrectName()

{

// Arrange

var name = "Davide";

// Act

var user = BuildUser(name, null, DateTime.Now, null, null);

// Assert

user.FirstName.Should().Be(name);

}

[Test]

public void BuildUser_Should_CreateUserWithCorrectLastName()

{

// Arrange

var lastName = "Bellone";

// Act

var user = BuildUser(null, lastName, DateTime.Now, null, null);

// Assert

user.LastName.Should().Be(lastName);

}

… and so on. Imagine writing a test for each property: your test class will be full of small methods that only clutter the code.

If you can group assertions in a logical way, you could write more asserts in a single test:

[Test]

public void BuildUser_Should_CreateUserWithCorrectPlainInfo()

{

// Arrange

var name = "Davide";

var lastName = "Bellone";

var birthDay = new DateTime(1991, 1, 1);

// Act

var user = BuildUser(name, lastName, birthDay, null, null);

// Assert

user.FirstName.Should().Be(name);

user.LastName.Should().Be(lastName);

user.BirthDate.Should().Be(birthDay);

}

This is fine because the three properties (FirstName, LastName, and BirthDate) are logically on the same level and with the same meaning.

One concept per test

As we stated before, it’s not important to test only one property per test: each and every test must be focused on a single concept.

By looking at the previous examples, you can notice that the AddressInfo property is built using the values passed as parameters on the BuildUser method. That makes it a good candidate for its own test.

Another way of seeing this tip is thinking of the properties of an object (I mean, the mathematical properties). If you’re creating your custom sorting, think of which properties can be applied to your method. For instance:

- an empty list, when sorted, is still an empty list

- an item with 1 item, when sorted, still has one item

- applying the sorting to an already sorted list does not change the order

and so on.

So you don’t want to test every possible input but focus on the properties of your method.

In a similar way, think of a method that gives you the number of days between today and a certain date. In this case, just a single test is not enough.

You have to test – at least – what happens if the other date:

- is exactly today

- it is in the future

- it is in the past

- it is next year

- it is February, the 29th of a valid year (to check an odd case)

- it is February, the 30th (to check an invalid date)

Each of these tests is against a single value, so you might be tempted to put everything in a single test method. But here you are running tests against different concepts, so place every one of them in a separate test method.

Of course, in this example, you must not rely on the native way to get the current date (in C#, DateTime.Now or DateTime.UtcNow). Rather, you have to mock the current date.

FIRST tests: Fast, Independent, Repeatable, Self-validating, and Timed

You’ll often read the word FIRST when talking about the properties of good tests. What does FIRST mean?

It is simply an acronym. A test must be Fast, Independent, Repeatable, Self-validating, and Timed.

Fast

Tests should be fast. How much? Enough to don’t discourage the developers to run them. This property applies only to Unit Tests: in fact, while each test should run in less than 1 second, you may have some Integration and E2E tests that take more than 10 seconds – it depends on what you’re testing.

Now, imagine if you have to update one class (or one method), and you have to re-run all your tests. If the whole tests suite takes just a few seconds, you can run them whenever you want – some devs run all the tests every time they hit Save; if every single test takes 1 second to run, and you have 200 tests, just a simple update to one class makes you lose at least 200 seconds: more than 3 minutes. Yes, I know that you can run them in parallel, but that’s not the point!

So, keep your tests short and fast.

Independent

Every test method must be independent of the other tests.

This means that the result and the execution of one method must not impact the execution of another one. Conversely, one method must not rely on the execution of another method.

A concrete example?

public class MyTests

{

string userName = "Lenny";

[Test]

public void Test1()

{

Assert.AreEqual("Lenny", userName);

userName = "Carl";

}

[Test]

public void Test2()

{

Assert.AreEqual("Carl", userName);

}

}

Those tests are perfectly valid if run in sequence. But Test1 affects the execution of Test2 by setting a global variable

used by the second method. But what happens if you run only Test2? It will fail. Same result if the tests are run in a different order.

So, you can transform the previous method in this way:

public class MyTests

{

string userName;

[SetUp]

public void Setup()

{

userName = "Boe";

}

[Test]

public void Test1()

{

userName = "Lenny";

Assert.AreEqual("Lenny", userName);

}

[Test]

public void Test2()

{

userName = "Carl";

Assert.AreEqual("Carl", userName);

}

}

In this way, we have a default value, Boe, that gets overridden by the single methods – only when needed.

Repeatable

Every Unit test must be repeatable: this means that you must be able to run them at any moment and on every machine (and get always the same result).

So, avoid all the strong dependencies on your machine (like file names, absolute paths, and so on), and everything that is not directly under your control: the current date and time, random-generated numbers, and GUIDs.

To work with them there’s only a solution: abstract them and use a mocking mechanism.

If you want to learn 3 ways to do this, check out my 3 ways to inject DateTime and test it. There I explained how to inject DateTime, but the same approaches work even for GUIDs and random numbers.

Self-validating

You must be able to see the result of a test without performing more actions by yourself.

So, don’t write your test results on an external file or source, and don’t put breakpoints on your tests to see if they’ve passed.

Just put meaningful assertions and let your framework (and IDE) tell you the result.

Timely

You must write your tests when required. Usually, when using TDD, you write your tests right before your production code.

So, this particular property applies only to devs who use TDD.

Wrapping up

In this article, we’ve seen that even if many developers consider tests redundant and not worthy of attention, they are first-class citizens of our applications.

Paying enough attention to tests brings us a lot of advantages:

- tests document our code, thus helping onboarding new developers

- they help us deploy with confidence a new version of our product, without worrying about regressions

- they prove that our code has no bugs (well, actually you’ll always have a few bugs, it’s just that you haven’t discovered them yet )

- code becomes more flexible and can be extended without too many worries

So, write meaningful tests, and always well written.

Quality over quantity, always!

Happy coding!

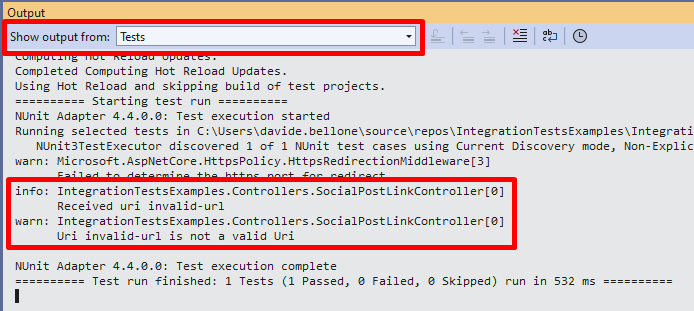

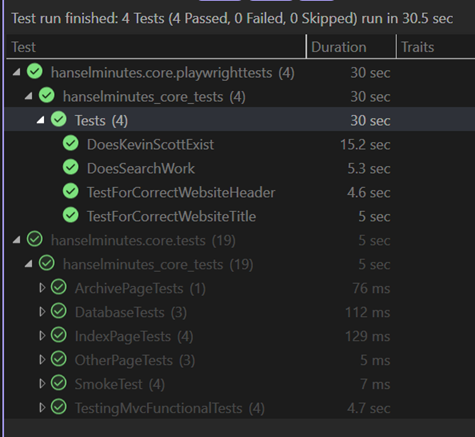

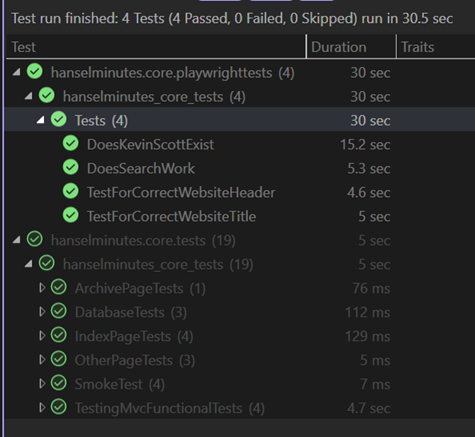

I’ve been doing not just Unit Testing for my sites but full on Integration Testing and Browser Automation Testing as early as 2007 with Selenium. Lately, however, I’ve been using the faster and generally more compatible

I’ve been doing not just Unit Testing for my sites but full on Integration Testing and Browser Automation Testing as early as 2007 with Selenium. Lately, however, I’ve been using the faster and generally more compatible