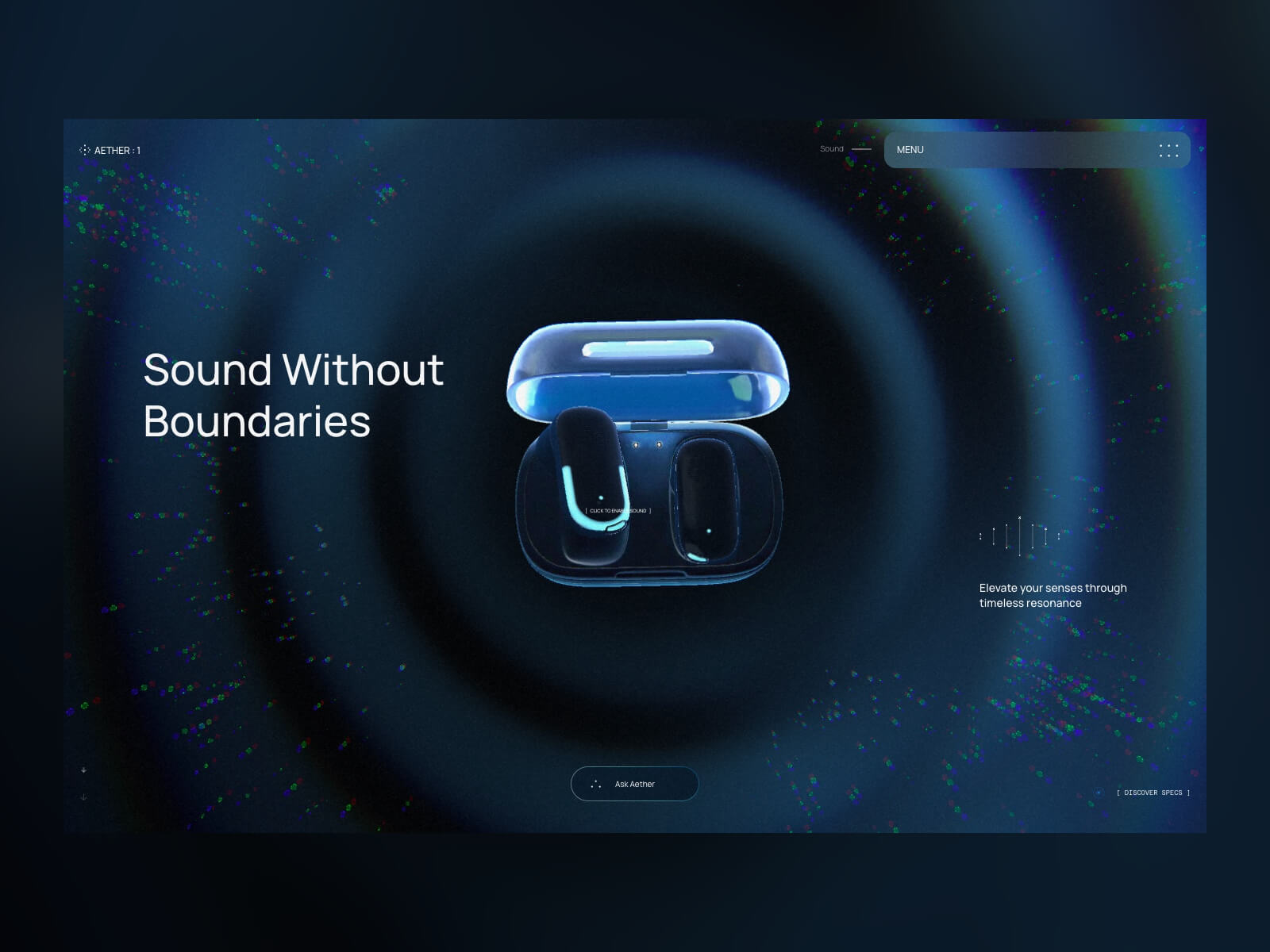

Aether 1 began as an internal experiment at OFF+BRAND: Could we craft a product‑launch site so immersive that visitors would feel the sound?

The earbuds themselves are fictional, but every pixel of the experience is real – an end‑to‑end sandbox where our brand, 3D, and engineering teams pushed WebGL, AI‑assisted tooling, and narrative design far beyond a typical product page.

This technical case study is the living playbook of that exploration. Inside you’ll find:

- 3D creation workflow – how we sculpted, animated, and optimised the earphones and their charging case.

- Interactive WebGL architecture – the particle flow‑fields, infinite scroll, audio‑reactive shaders, and custom controllers that make the site feel alive.

- Performance tricks – GPU‑friendly materials, faux depth‑of‑field, selective bloom, and other tactics that kept the project running at 60 FPS on mobile hardware.

- Tool stack & takeaways – what worked, what didn’t, and why every lesson here can translate to your own projects.

Whether you’re a developer, designer, or producer, the next sections unpack the decisions, experiments, and hard‑won optimizations that helped us prove that “sound without boundaries” can exist on the web.

1. 3D Creation Workflow

By Celia Lopez

3D creation of the headphone and case

For the headphone shape, we needed to create one from scratch. To help ourselves quickly sketch out the ideas we had in mind, we used Midjourney. Thanks to references from the internet and the help of AI, we agreed on an artistic direction.

Size reference and headphone creation

To ensure the size matched a real-life reference, we used Apple headphones and iterated until we found something interesting. We used Figma to present all the iterations to the team, exporting three images – front, side, and back – each time to help them better visualize the object.

Same for the case.

Storyboard

For the storyboard, we first sketched our ideas and tried to match each specific scene with a 3D visualization.

We iterated for a while before finalizing the still frames for each part. Some parts were too tricky to represent in 3D, so we adjusted the workflow accordingly.

Motion

So that everyone agrees on the flow, look, and feel, we created a full-motion version of it.

Unwrapping and renaming

To prepare the scene for a developer, we needed to spend some time unwrapping the UVs, cleaning the file, and renaming the elements. We used C4D exclusively for unwrapping since the shapes weren’t too complex. It’s also very important to rename all parts and organize the file so the developer can easily recognize which object is which. (In the example below, we show the technique – not the full workflow or a perfect unwrap.)

Fluid flow baked

Almost all the animations were baked from C4D to Blender and exported as .glb files.

Timing

We decided to start with an infinite scroll and a looped experience. When the user releases the scroll, seven anchors subtly and automatically guide the progression. To make it easier for the developer to divide the baked animation, we used specific timing for each step — 200 keyframes between each anchor.

AO baking

Because the headphones were rotating, we couldn’t bake the lighting. We only baked the Ambient Occlusion shadows to enhance realism. For that, after unwrapping the objects, we combined all the different parts of the headphones into a single object, applied a single texture with the Ambient Occlusion, and baked it in Redshift. Same for the case.

Normal map baked

For the Play‑Stade touchpad only, we needed a normal map, so we exported it. However, since the AO was already baked, the UVs had to remain the same.

Camera path and target

In order to ensure a smooth flow during the web experience, it was crucial to use a single camera. However, since we have different focal points, we needed two separate circular paths with different centers and sizes, along with a null object to serve as a target reference throughout the flow.

2. WebGL Features and Interactive Architecture

By Adrian Gubrica

GPGPU particles

Particles are a great way to add an extra layer of detail to 3D scenes, as was the case with Aether 1. To complement the calming motion of the audio waves, a flow‑field simulation was used — a technique known for producing believable and natural movement in particle systems. With the right settings, the resulting motion can also be incredibly relaxing to watch.

To calculate the flow fields, noise algorithms — specifically Simplex4D — were used. Since these can be highly performance-intensive on the CPU, a GPGPU technique (essentially the WebGL equivalent of a compute shader) was implemented to run the simulation efficiently on the GPU. The results were stored and updated across two textures, enabling smooth and high-performance motion.

Smooth scene transitions

To create a seamless transition between scenes, I developed a custom controller to manage when each scene should or shouldn’t render. I also implemented a manual way of controlling their scroll state, allowing me, for example, to display the last position of a scene without physically scrolling there. By combining this with a custom transition function that primarily uses GSAP to animate values, I was able to create both forward and backward animations to the target scene.

It is important to note that all scenes and transitions are displayed within a “post‑processing scene,” which consists of an orthographic camera and a full‑screen plane. In the fragment shader, I merge all the renders together.

This transition technique became especially tricky when transitioning at the end of each scroll in the main scene to create an infinite loop. To achieve this, I created two instances of the main scene (A and B) and swapped between them whenever a transition occurred.

Custom scroll controller for infinite scrolling

As mentioned earlier, the main scene features an infinite loop at both the start and end of the scroll, which triggers a transition back to the beginning or end of the scene. This behavior is enhanced with some resistance during the backward movement and other subtle effects. Achieving this required careful manual tweaking of the Lenis library.

My initial idea was to use Lenis’ infinite: true property, which at first seemed like a quick solution – especially for returning to the starting scroll position. However, this approach required manually listening to the scroll velocity and predicting whether the scroll would pass a certain threshold to stop it at the right moment and trigger the transition. While possible, it quickly proved unreliable, often leading to unpredictable behavior like broken scroll states, unintended transitions, or a confused browser scroll history.

Because of these issues, I decided to remove the infinite: true property and handle the scroll transitions manually. By combining Lenis.scrollTo(), Lenis.stop(), and Lenis.start(), I was able to recreate the same looping effect at the end of each scroll with greater control and reliability. An added benefit was being able to retain Lenis’s default easing at the beginning and end of the scroll, which contributed a smooth and polished feel.

Cursor with fluid simulation pass

Fluid simulation triggered by mouse or touch movement has become a major trend on immersive websites in recent years. But beyond just being trendy, it consistently enhances the visual appeal and adds a satisfying layer of interactivity to the user experience.

In my implementation, I used the fluid simulation as a blue overlay that follows the pointer movement. It also served as a mask for the Fresnel pass (explained in more detail below) and was used to create a dynamic displacement and RGB shift effect in the final render.

Because fluid simulations can be performance‑intensive – requiring multiple passes to calculate realistic behavior – I downscaled it to just 7.5 percent of the screen resolution. This optimization still produced a visually compelling effect while maintaining smooth overall performance.

Fresnel pass on the earphones

In the first half of the main scene’s scroll progression, users can see the inner parts of the earphones when hovering over them, adding a nice interactive touch to the scene. I achieved this effect by using the fluid simulation pass as a mask on the earphones’ material.

However, implementing this wasn’t straightforward at first, since the earphones and the fluid simulation use different coordinate systems. My initial idea was to create a separate render pass for the earphones and apply the fluid mask in that specific pass. But this approach would have been costly and introduced unnecessary complexity to the post‑processing pipeline.

After some experimentation, I realized I could use the camera’s view position as a kind of screen‑space UV projection onto the material. This allowed me to accurately sample the fluid texture directly in the earphones’ material – exactly what I needed to make the effect work without additional rendering overhead.

Audio reactivity

Since the project is a presentation of earphones, some scene parameters needed to become audio‑reactive. I used one of the background audio’s frequency channels – the one that produced the most noticeable “jumps,” as the rest of the track had a very stable tone – which served as the input to drive various effects. This included modifying the pace and shape of the wave animations, influencing the strength of the particles’ flow field, and shaping the touchpad’s visualizer.

The background audio itself was also processed using the Web Audio API, specifically a low‑pass filter. This filter was triggered when the user hovered over the earphones in the first section of the main scene, as well as during the scene transitions at the start and end. The low‑pass effect helped amplify the impact of the animations, creating a subtle sensation of time slowing down.

Animation and empties

Most of the animations were baked directly into the .glb file and controlled via the scroll progress using THREE.js’s AnimationMixer. This included the camera movement as well as the earphone animations.

This workflow proved to be highly effective when collaborating with another 3D artist, as it gave them control over multiple aspects of the experience – such as timing, motion, and transitions – while allowing me to focus solely on the real‑time interactions and logic.

Speaking of real‑time actions, I extended the scene by adding multiple empties, animating their position and scale values to act as drivers for various interactive events – such as triggering interactive points or adjusting input strength during scroll. This approach made it easy to fine‑tune these events directly in Blender’s timeline and align them precisely with other baked animations.

3. Optimization Techniques

Visual expectations were set very high for this project, making it clear from the start that performance optimization would be a major challenge. Because of this, I closely monitored performance metrics throughout development, constantly looking for opportunities to save resources wherever possible. This often led to unexpected yet effective solutions to problems that initially seemed too demanding or impractical for our goals. Some of these optimizations have already been mentioned – such as using GPGPU techniques for particle simulation and significantly reducing the resolution of the cursor’s fluid simulation. However, there were several other key optimizations that played a crucial role in maintaining solid performance:

Artificial depth of field

One of that was using depth of field during the close‑up view on the headphones. Depth of field is usually used as a post‑processing layer using some kind of convolution to simulate progressive blurring of the rendered scene. I considered this as a good‑to‑have from the beginning in case we will be left with some additional fps, but not as a realistic option.

However, after implementing the particles simulation, which used smoothstep function in the particle’s fragment shader to draw the blue circle, I was wondering if it might not be enough to simply modify its values to make it look like it’s blurred. After few little tweaks, the particles became blurry.

The only problem left was that the blur was not progressive like in a real camera, meaning it was not getting blurry according to the focus point of the camera. So I decided to try the camera’s view position to get some kind of depth value, which surprisingly did the job well.

I applied the same smoothstep technique to the rotating tube in the background, but now without the progressive effect since it was almost at a constant distance most of the time.

Voilà. Depth of field for almost free (not perfect, but does the job well).

Artificial bloom

Bloom was also part of the post‑processing stack – typically a costly effect due to the additional render pass it requires. This becomes even more demanding when using selective bloom, which I needed to make the core of the earphones glow. In that case, the render pass is effectively doubled to isolate and blend only specific elements.

To work around this performance hit, I replaced the bloom effect with a simple plane using a pre‑generated bloom texture that matched the shape of the earphone core. The plane was set to always face the camera (a billboard technique), creating the illusion of bloom without the computational overhead.

Surprisingly, this approach worked very well. With a bit of fine‑tuning – especially adjusting the depth write settings – I was even able to avoid visible overlaps with nearby geometry, maintaining a clean and convincing look.

Custom performant glass material

A major part of the earphones’ visual appeal came from the glossy surface on the back. However, achieving realistic reflections in WebGL is always challenging – and often expensive – especially when using double‑sided materials.

To tackle this, I used a strategy I often rely on: combining a MeshStandardMaterial for the base physical lighting model with a glass matcap texture, injected via the onBeforeCompile callback. This setup provided a good balance between realism and performance.

To enhance the effect further, I added Fresnel lighting on the edges and introduced a slight opacity, which together helped create a convincing glass‑like surface. The final result closely matched the visual concept provided for the project – without the heavy cost of real‑time reflections or more complex materials.

Simplified raycasting

Raycasting on high‑polygon meshes can be slow and inefficient. To optimise this, I used invisible low‑poly proxy meshes for the points of interest – such as the earphone shapes and their interactive areas.

This approach significantly reduced the performance cost of raycasting while giving me much more flexibility. I could freely adjust the size and position of the raycastable zones without affecting the visual mesh, allowing me to fine‑tune the interactions for the best possible user experience.

Mobile performance

Thanks to the optimisation techniques mentioned above, the experience maintains a solid 60 FPS – even on older devices like the iPhone SE (2020).

- Three.js: For a project of this scale, Three.js was the clear choice. Its built‑in materials, loaders, and utilities made it ideal for building highly interactive WebGL scenes. It was especially useful when setting up the GPGPU particle simulation, which is supported via a dedicated addon provided by the Three.js ecosystem.

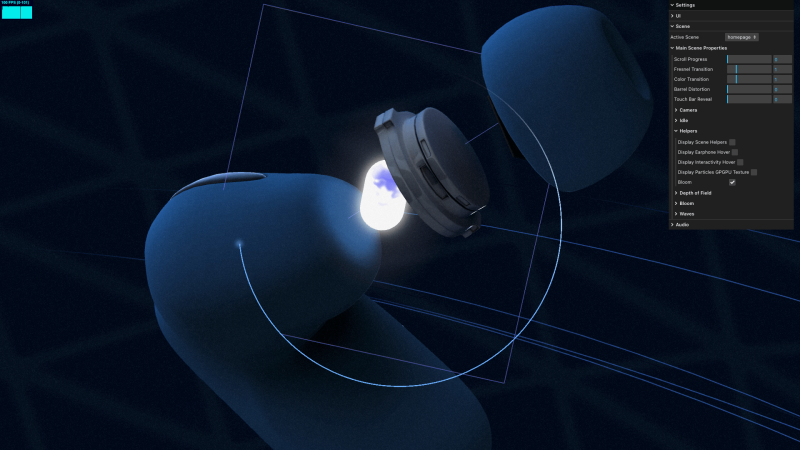

- lil‑gui: Commonly used alongside Three.js, was instrumental in creating a debug environment during development. It also allowed designers to interactively tweak and fine‑tune various parameters of the experience without needing to dive into the code.

- GSAP: Most linear animations were handled with GSAP and its timeline system. It proved particularly useful when manually syncing animations to the scroll progress provided by Lenis, offering precise control over timing and transitions.

- Lenis: As mentioned earlier, Lenis provided a smooth and reliable foundation for scroll behavior. Its

syncTouchparameter helped manage DOM shifting on mobile devices, which can be a common challenge in scroll‑based experiences.

5. Results and Takeaways

Aether 1 successfully demonstrated how brand narrative, advanced WebGL interactions, and rigorous 3D workflows can blend into a single, performant, and emotionally engaging web experience.

By baking key animations, using empties for event triggers, and leaning on tools like Three.js, GSAP, and Lenis, the team was able to iterate quickly without sacrificing polish. Meanwhile, the 3D pipeline- from Midjourney concept sketches through C4D unwrapping and Blender export ensured the visual fidelity stayed aligned with the brand vision.

Most importantly, every technique outlined here is transferable. Whether you are considering audio‑reactive visuals, infinite scroll adventures, or simply trying to squeeze extra frames per second out of a heavy scene, the solutions documented above show that thoughtful planning and a willingness to experiment can push WebGL far beyond typical product‑page expectations.

6. Author Contributions

General – Ross Anderson

3D – Celia Lopez

WebGL – Adrian Gubrica

7. Site credits

Art Direction – Ross Anderson

Design – Gilles Tossoukpe

3D – Celia Lopez

WebGL – Adrian Gubrica

AI Integration – Federico Valla

Motion – Jason Kearley

Front End / Webflow – Youness Benammou